- Proud to be a part of this glorious page of military history

Group Captain Ashok K Chordia (Retd)

New Delhi. 26 April 2020. It has been more than a quarter of a century since that chapter of glorious Indian military history was written. Memory of that day––as time flew and the events unfolded on Thursday, November the 3rd, 1988 ––is etched indelibly in my mind.

I was then a young Flight Lieutenant, a fully operational Parachute Jump Instructor (PJI) and a Combat Freefaller posted at the Paratroopers’ Training School, Agra. That November day was going to be my big day. I had been detailed to lead a skydiving demonstration at the National Defence Academy (NDA), Pune and was awaiting airlift for my team along with the parachutes and other equipment. The very idea of leading Akashganga––the IAF’s Skydiving Team––at a demonstration at my alma mater was exhilarating to say the least. Way ahead of the body, my mind had soared to the Academy and had already perambulated twice between Juliet Squadron (my home for three years when I was a cadet at the NDA more than a dozen years ago) and the picturesque Peacock Bay. My reverie was broken when a Warrant Officer told me that the movement to NDA Khadakwasla had been put on hold. Also, there was a change in programme, and the team had been reorganised––my name was conspicuously missing from the list of skydivers.

Hours later, I found myself on board ‘Friendly One’, the lead aircraft in the two aircraft formation––flown by the legendary duo of Group Captains AG Bewoor and AK Goel––heading for Malé. Also on board were: Brigadier FFC (Bull) Bulsara, the Para Brigade Commander; Colonel SC (Joe) Joshi, Commanding Officer, 6 Para Battalion; Major RJS Dhillon (Company Commander Charlie Company) and a whole lot of others. With paratroopers and parachutes around me in an aircraft in-flight, I knew my raison d’être, as always, was to prepare them and ‘help’ them out of the exit door on the “Green” signal.

There was a high degree of secrecy; people were being briefed on a need-to-know basis. So, going by the antecedents, I had presumed that we were going to launch an airborne operation in Sri Lanka. The memory of a month long wait with 10 Para SF, a couple of months ago, in Sulur was fresh in my mind. The airborne operation in that instance had been called off; 10 Para were inducted into Sri Lanka in the routine sorties. The sight of Mr AK Banerjee, the Indian High Commissioner to the Maldives, sitting pensively in the row of seats behind the aircrew and my interaction with others soon after take off, put things in perspective for me.

Based on favourable inputs with regards to the security of the runway for landing, and considering the limitations of the possible drop zone (Hulule Airfield), a paradrop was done away with––we were going to land. There was heightened anxiety in the cockpit as the aircrew prepared for ‘the’ landing of their lifetime––on an unfamiliar runway, barely (long) enough to accommodate the landing run of the Mighty Jet (an epithet given to the IL-76 aircraft of 44 Squadron), in the dark of the night after a gruelling four-hour flight with practically no landing aids… the runway lights coming ‘ON’ only momentarily. Not to talk of the remote possibility of encountering enemy fire on touchdown.Viva! Group Captains Bewoor and Goel, some nerves!

The prospect of a fight breaking out between the landing force and the rebels who were still active in the archipelago could not be ruled out. A contest for the control of the airfield would possibly prevent the landing of the subsequent waves of aircraft (several were to follow). So I too deplaned with the troops with a redefined role: to control a para drop sitting on the ground, if a situation arose later. Now, all that is POSTSCRIPT; nothing of that nature happened.

Daringly, Major Dhillon and others of his ilk got into speedboats and assaulted the island of Malé. Meanwhile, I remember eerily, the exchange of fire between the rebels fleeing with hostages on board MV Progress Light, and our troops on Hulule airfield. Guns boomed and bullets flew as Warrant Officer Karam Singh (a PJI who was to assist me) and I, both unarmed––ran for cover behind the Air Traffic Control building. Well before dawn, the President was rescued, provided a human shield and escorted to a safe location.

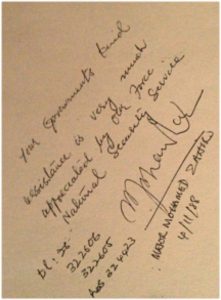

Next morning, my curiosity took me to Malé in a speedboat. I saw the walls of the Headquarters of the National Security Service (NSS) of the Maldives that bore testimony to the havoc that had been let loose on the city by the terrorists over the preceding day. There I met Major Mohammed Zahir, a senior officer of the NSS who, in a gesture of unadulterated gratitude for the Indians wrote the following note for me:

“Your Government’s kind assistance is very much appreciated by our Force. National Security Service.” Signed Major Mohammed Zahir November 4, 1988.

He also gave me his cap badge and his formation sign, which along with the memories of the eventful night spent in the Maldives, are among the most valuable of all my possessions.

A coup attempt in the Maldives in November 1988––by Abdullah Luthufee, a Maldivian businessman, supported by the Sri Lanka based terror outfit, the People’s Liberation Organisation of Tamil Elam led by Maheswaran––forced President Maumoon Abdul Gayoom to go into hiding. Malé flashed SOS messages to the US, the UK, Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan and several other countries of the British Commonwealth, seeking military assistance to quell the putsch. In their moment of crisis, when the Maldivians needed prompt action and when most countries were contemplating whether or not to respond, Indian paratroopers landed on the islands as saviours and provided succour. Operation Cactus, as it came to be known, is one of the most daring military operations ever undertaken by armed forces anywhere in the world. People have likened it to Operation Eiche––the rescue of Benito Mussolini by the Germans (Italy, 1943). Some others have pointed at its similarities with Operation Thunderbolt (later renamed, Netanyahu)––the rescue of 104 hostages by the Israel’s airborne troops (Entebbe, 1976).

Launched at a very short notice, Operation Cactus was a race against time––the Indian troops had to reach Malé and find President Gayoom before the rebels could locate him. The gun-toting terrorists were already prowling the streets of the island capital measuring barely 2 sq kms when the SOS messages reached India. If the rebels were to find President Gayoom before arrival of the Indian troops, and if they could gain control of Malé, then there would be a twist in the tale. A rogue government hoisted by Abdullah Luthufee would possibly consider the arrival of the Indian troops––a case of unsolicited assistance. Even worse, it could be construed as an act of aggression against a sovereign state.

The decision to launch an airborne operation 2600 kms away in the Maldives was a difficult politico-military choice. India’s pre-occupation in Sri Lanka and the military setbacks in Jaffna in the preceding year must have weighed heavily on Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s mind. Yet the sound advice of the diplomatic corps, and the confidence and assurance of the military leadership of the day enabled Mr Rajiv Gandhi to give a go ahead.

In response to Delhi’s clarion call, the paratroopers of 50(I) Para Brigade got into action. The IAF airlifted them to rescue the President and secure the islands. Later, the Indian Navy chased the rebels––who had hijacked a merchant vessel and had fled, taking seven hostages on board––and coerced them into surrender.The rest is history.

It is a fact that there were no maps; there was very little intelligence; the notice was short, …the men were scattered––the list of handicaps on the eve of the launch of Operation Cactus is long; very long, indeed. Owing to the extreme uncertainties, most pundits, and the strategic thinkers (of that time) would have forecast failure. Even to this day, some people opine that the decision to embark on this mission was ill conceived, and that it could well have been avoided––there was no justifiable need for India to volunteer to pull Malé’s chestnuts out of the fire.

For long, mainly due to lack of knowledge of the facts, many have maintained that Indians went into the Operation ill planned and ill prepared. Of course, everyone is entitled to an opinion, but the fact is that we did not sleepwalk into the Maldives. It was a deliberate and sufficiently contemplated mission––contingencies had been catered for, including abandoning the Operation and returning to Trivandrum, if the situation so demanded. The decision was followed up by prompt military action. The resources, and the capabilities were limited but the ability to exploit those resources was tremendous––what was achieved was perhaps the best that could have been done under those circumstances.

Operation Cactus underscores three fundamental issues: One, success of military operations depends on innumerable factors. Two, all such factors cannot possibly align and converge favourably, at one point in the time of crisis. And three, in the words of Anthony S Cordesman: “There are times to take well-reasoned risks, and victory is its own validation.” Operation Cactus is the saga of men determined to achieve ends despite innumerable odds. It proved the prowess of the Indian military and diplomacy alike and showcased India as an emerging Regional Power.

Group Captain Ashok K Chordia (Retd) is the Author of Operation Cactus: Anatomy of one of India’s Most Daring Military Operations. The views in the article are his. He will be available at akchordia@gmail.com.