- August 6, 1945 – August 6, 2025: Hiroshima’s Long Shadow

By Sangeeta Saxena

New Delhi. 06 August 2025. It has been six years since I took the biggest pilgrimage of my life . For a daughter of a nuclear physicist two cities and the horror they went through, were always a part of my growing up conversations with my father. And suddenly in 2019 I asked him if he wanted to visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki and his counter question – is it possible? – made me take the trip of my life.

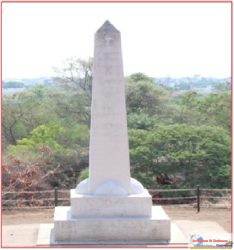

Time came to a standstill at 8.15 AM on 6th August 1945 for the city of Hiroshima. It has been 80 years since the city saw the most horrific sight , the scars of which are still visible. But the city rose like a phoenix from its ashes and decided to reconstruct itself as a state-of-the-art modern city in tranquillity. It decide to build a Peace Park at the hypocenter which is the location on the ground directly below the center of the explosion which was only a few hundred yards east of the bridge, which is now the peace bridge. Many monuments were decided to be built to mark the bombing and symbolize peace in the world. One of these monuments is Hiroshima Peace Flame dedicated to the victims of Hiroshima and has been burning continuously since it was lit in on August 1, 1964 .

Time came to a standstill at 8.15 AM on 6th August 1945 for the city of Hiroshima. It has been 80 years since the city saw the most horrific sight , the scars of which are still visible. But the city rose like a phoenix from its ashes and decided to reconstruct itself as a state-of-the-art modern city in tranquillity. It decide to build a Peace Park at the hypocenter which is the location on the ground directly below the center of the explosion which was only a few hundred yards east of the bridge, which is now the peace bridge. Many monuments were decided to be built to mark the bombing and symbolize peace in the world. One of these monuments is Hiroshima Peace Flame dedicated to the victims of Hiroshima and has been burning continuously since it was lit in on August 1, 1964 .

The A-Bomb Dome is the skeletal ruins of the former Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall. It is the building closest to the hypocenter of the nuclear bomb that remained at least partially standing. It was left how it was after the bombing in memory of the casualties.The A-Bomb Dome is a symbol of peace which most people have at least seen at one time in a picture.

But very few know that the initial choice for the first bombing was Kyoto which was a large industrial city with a population of more than a million, the biggest cultural and intellectual center and the ancient capital of Japan. Aim of the Allied Forces was – One bomb, from one plane, would wipe a city off the map, should so horrible that it would end the war and create a permanent fear in the world towards the future use of nuclear bombs. The only point which went against it and gave Hiroshima place in world history was Kyoto had no significant military installations. About 25,000 troops were believed to have been stationed there at the time of the blast.

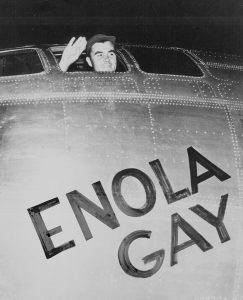

Eighty years ago, on the morning of August 6, 1945, the Japanese city of Hiroshima was reduced to rubble in a matter of seconds. At 8:15 a.m., the Enola Gay, a U.S. B-29 bomber, dropped the world’s first atomic bomb—nicknamed Little Boy—forever changing the course of history. As the bomb exploded approximately 600 meters above the ground, it unleashed a blinding flash, a wave of heat that incinerated everything within a mile radius, and a deadly shockwave that flattened buildings. By the end of the day, over 70,000 people were dead, and tens of thousands more would succumb in the weeks and years that followed to radiation sickness, burns, and trauma.

Eighty years ago, on the morning of August 6, 1945, the Japanese city of Hiroshima was reduced to rubble in a matter of seconds. At 8:15 a.m., the Enola Gay, a U.S. B-29 bomber, dropped the world’s first atomic bomb—nicknamed Little Boy—forever changing the course of history. As the bomb exploded approximately 600 meters above the ground, it unleashed a blinding flash, a wave of heat that incinerated everything within a mile radius, and a deadly shockwave that flattened buildings. By the end of the day, over 70,000 people were dead, and tens of thousands more would succumb in the weeks and years that followed to radiation sickness, burns, and trauma.

What makes the atomic bombing of Hiroshima so significant is not just its scale of destruction, but the fact that it marked humanity’s entry into the nuclear age—a moment when science’s promise of progress collided with the brutal calculus of war. The decision to drop the bomb remains one of the most controversial acts in modern history, justified by some as a means to end World War II quickly, but condemned by others as an unjustifiable act of mass slaughter.

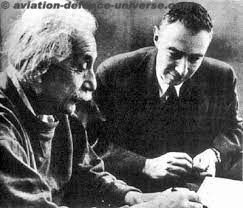

The seeds of this devastation were sown not in a war room, but in a scientific formula. It was Albert Einstein’s iconic equation, E=MC², that provided the theoretical foundation for nuclear energy. The equation, which states that energy (E) equals mass (m) times the speed of light squared (c²), revealed that even a small amount of mass could be converted into an immense amount of energy. Though Einstein himself was a pacifist, he co-signed a 1939 letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt warning that Nazi Germany might be developing atomic weapons—this letter helped trigger the Manhattan Project, the top-secret U.S. initiative to build the bomb. Ironically, Einstein was not involved in the bomb’s development, yet his equation became the scientific bedrock that made nuclear fission a terrifying reality.

Today, Hiroshima stands as a solemn city of remembrance and resilience. The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, the Genbaku Dome, and the annual August 6th ceremonies serve as stark reminders of what nuclear warfare can bring—and a warning to future generations. Survivors, known as Hibakusha, continue to share their stories, urging the world to remember not just the pain, but also the enduring hope for peace. Their voices grow fainter with time, but their message remains urgent.

Out of all the bombed buildings in Hiroshima one of the lesser known and rarely visited is the Hiroshima Municipal Girls High School. As soon as one crosses the Peace Bridge on the right is the Peace Memorial Park and on the left is a figure of the girl engraved in the centre carrying a box carved with the formula for nuclear energy: E=MC² . The formula is taken from Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, the principle behind the atomic bomb. The indirect expression was a way around the occupation army’s prohibition on using the characters for “atomic bombing.”

Out of all the bombed buildings in Hiroshima one of the lesser known and rarely visited is the Hiroshima Municipal Girls High School. As soon as one crosses the Peace Bridge on the right is the Peace Memorial Park and on the left is a figure of the girl engraved in the centre carrying a box carved with the formula for nuclear energy: E=MC² . The formula is taken from Albert Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, the principle behind the atomic bomb. The indirect expression was a way around the occupation army’s prohibition on using the characters for “atomic bombing.”

The Memorial Monument to the Victims of Atomic bomb completed on August 6, 1948 established by bereaved families of Hiroshima Municipal Girl’s High School. All of the 544 first and second year students and 8 teachers of Hiroshima Municipal Girl’s High School who were working on building demolition in the vicinity of the south end of present Peace Memorial Park and Peace Boulevard perished. This area, which is 500 meters from the hypocenter, was in Zaimoku-cho and Kobiki-cho at the time. Including students mobilized at other places in the city, the school lost 679 people, the most of any school in the city. On the back of the monument is engraved, “Rest in peace within this grassy hill. Protected by a wall of friends.” The writer was Masaomi Miyakawa, who was principal at the time.

There were 90,000 buildings in Hiroshima before the bomb was dropped; only 28,000 remained after the bombing. Over 90% of Hiroshima’s doctors and 93% of its nurses were killed. 30% of Hiroshima’s population was killed immediately, with about 30% more wounded. At the time of its bombing, Hiroshima was a city of both industrial and military significance. A number of military units were located nearby, the most important of which was the headquarters of Field Marshal Shunroku Hata’s Second General Army, which commanded the defense of all of southern Japan, and was located in Hiroshima Castle. Hata’s command consisted of some 400,000 men, most of whom were on Kyushu where an Allied invasion was correctly anticipated. Also present in Hiroshima were the headquarters of the 59th Army, the 5th Division and the 224th Division, a recently formed mobile unit. The city was defended by five batteries of 7-cm and 8-cm (2.8 and 3.1 inch) anti-aircraft guns of the 3rd Anti-Aircraft Division, including units from the 121st and 122nd Anti-Aircraft Regiments and the 22nd and 45th Separate Anti-Aircraft Battalions. In total, an estimated 40,000 Japanese military personnel were stationed in the city.

Hiroshima was a minor supply and logistics base for the Japanese military, but it also had large stockpiles of military supplies.The city was also a communications center, a key port for shipping and an assembly area for troops. It was also the second largest city in Japan after Kyoto that was still undamaged by air raids, due to the fact that it lacked the aircraft manufacturing industry that was the XXI Bomber Command’s priority target. On July 3, the Joint Chiefs of Staff placed it off limits to bombers, along with Kokura, Niigata and Kyoto.

Hiroshima was a minor supply and logistics base for the Japanese military, but it also had large stockpiles of military supplies.The city was also a communications center, a key port for shipping and an assembly area for troops. It was also the second largest city in Japan after Kyoto that was still undamaged by air raids, due to the fact that it lacked the aircraft manufacturing industry that was the XXI Bomber Command’s priority target. On July 3, the Joint Chiefs of Staff placed it off limits to bombers, along with Kokura, Niigata and Kyoto.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, located within the Hiroshima Peace Memorial, had been established in August 1955 alongside the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Hall, now known as the International Conference Center Hiroshima. The museum collected and displayed belongings left behind by the victims, photographs, and other materials that conveyed the horror of the atomic bombing. These exhibits were thoughtfully supplemented by displays that depicted Hiroshima before and after the blast, along with others that explored the contemporary state of the nuclear age. Every item on display embodied the grief, anger, or pain of real people whose lives had been forever changed.

Hiroshima had truly become a city of peace in every sense. I walked along Peace Boulevard, a 4km-long avenue lined with trees and stone lanterns, passed through the Peace Memorial Park, and stood before the Gates of Peace, a series of 9m-high glass arches inscribed with the word ‘peace’ in 49 languages. What surprised me the most were the bicycles running on motors that locals affectionately called ‘peacecles’—a symbol of how seamlessly peace had been integrated into daily life.

Hiroshima had truly become a city of peace in every sense. I walked along Peace Boulevard, a 4km-long avenue lined with trees and stone lanterns, passed through the Peace Memorial Park, and stood before the Gates of Peace, a series of 9m-high glass arches inscribed with the word ‘peace’ in 49 languages. What surprised me the most were the bicycles running on motors that locals affectionately called ‘peacecles’—a symbol of how seamlessly peace had been integrated into daily life.

It had been the most agonising battle track I had ever undertaken in my career as a defence journalist—walking among the remnants and echoes of that horrific blast. Yet, Hiroshima of today proved to be equally motivating. The city inspired me deeply and infused a sense of positivity I hadn’t anticipated. It taught me that one must never assume that the end is final—for in Hiroshima, I witnessed a profound truth: the end is always a new beginning.

As the world marks the 80th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing, we are reminded of the fragility of peace in a world still bristling with nuclear arsenals. Hiroshima is not just a page in a history book—it is a mirror, asking us what kind of future we wish to build. The science that once made the bomb possible must now light the way toward disarmament and diplomacy, before another city suffers the same fate.