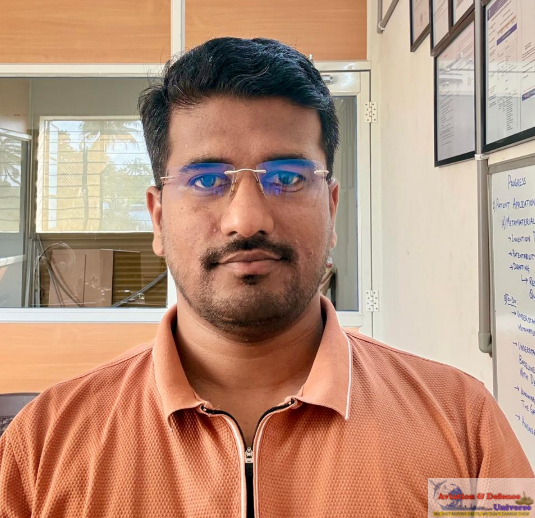

- Fighting the Enemy in the Air: Toyota chassis based vehicle

- Sets New Benchmark in Counter-Drone Technology

- From Borders to Cities: It Redefines India’s Response to Rogue Drones

By Sangeeta Saxena

Hyderabad. 29 November 2025. So we continue with our Indrajaal story. At T-Hub, India’s flagship innovation hub, homegrown defence-tech company not only formally unveiled Indrajaal Ranger, a next-generation anti-drone patrol vehicle built on its autonomous C-UAS (Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems) platform but the company’s leadership fielded an extended round of questions from defence journalists and analysts, offering a deep look into the thinking, technology and roadmap behind what they describe as a platform, not just a product.

Hyderabad. 29 November 2025. So we continue with our Indrajaal story. At T-Hub, India’s flagship innovation hub, homegrown defence-tech company not only formally unveiled Indrajaal Ranger, a next-generation anti-drone patrol vehicle built on its autonomous C-UAS (Counter-Unmanned Aerial Systems) platform but the company’s leadership fielded an extended round of questions from defence journalists and analysts, offering a deep look into the thinking, technology and roadmap behind what they describe as a platform, not just a product.

Indrajaal’s Founder & CEO, Kiran Penumacha , stressed that Ranger is a manifestation of a larger design philosophy. It is a platform, not a One-Off Vehicle, he stressed. The Ranger, he explained, is built on the Indrajaal platform, which has been architected for long-term evolution rather than single-generation use. The core stack—autonomy, power management, communications and computing—remains stable, while the sensor and effectors layer can be continuously upgraded as drone and threat technologies evolve.

The company is already working on multiple upgrade paths for the platform to keep it aligned with future threat patterns, including more advanced drone swarms, smarter RF behaviours and evolving electronic warfare techniques.

In parallel, Indrajaal is exploring “capability as a service” models for certain customers. Under such arrangements, the system remains owned and continually upgraded by Indrajaal, while the user pays for the capability rather than taking on long-term ownership, integration and lifecycle headaches.

In parallel, Indrajaal is exploring “capability as a service” models for certain customers. Under such arrangements, the system remains owned and continually upgraded by Indrajaal, while the user pays for the capability rather than taking on long-term ownership, integration and lifecycle headaches.

One theme came through clearly: the company does not wait for a formal requirement to start building.

Indrajaal’s approach is to spot the problem early, build ahead of demand, and then take the solution to the user. Ranger itself, they emphasised, was not driven by a specific RFP—but by an observed and growing operational gap on India’s borders and in its hinterland.

With militaries like the US Navy exploring hydrogen fuel cells for drone endurance, questions naturally turned to power systems. Indrajaal clarified that Ranger is a ground-based counter-drone platform, not an endurance drone in itself. Hydrogen cells make more sense for air platforms where long flight time is the core requirement.

Given the diversity of Indian forces—from the Army and BSF to state police and CAPFs—journalists asked if the Ranger system could be mounted on different vehicle platforms.

Indrajaal confirmed that the system is fundamentally vehicle-agnostic, but with engineering constraints. The host platform must meet minimum requirements in payload capacity, power availability, structural integrity for mounting masts and equipment, and stability for sensor and jammer operation.

Within those parameters, the system can be adapted to different 4×4 or specialised vehicles depending on the user: a ruggedised platform for borders and canals, a more urban-friendly platform for city policing, and heavier variants for high-threat zones.

Operational commanders, especially in the Army, are concerned not just with what a system can see—but how visible it is to the enemy. On this, Indrajaal highlighted a key design choice: Ranger does not function like a radar. It relies primarily on passive RF detection, meaning it listens rather than constantly transmitting. That dramatically reduces its electronic signature and makes it difficult for enemy electronic warfare systems to locate.

On integration with tanks and armoured fighting vehicles, the company acknowledged a different design space. Heavy armour assets such as tanks come with their own active protection systems (APS) and layered defences.

Indrajaal sees its counter-drone capabilities as one element in a broader protective ecosystem, not a standalone shield for ₹100-crore assets. Work is already underway on tank and IFV-oriented variants, but those are separate engineering programmes with higher protection and integration requirements.

Another interesting point of discussion was whether Ranger’s visible presence—lights, markings, a recognisable silhouette—might make it more vulnerable than a dug-in, camouflaged fixed system. Indrajaal’s view is that patrol systems and fixed site systems play fundamentally different psychological and operational roles. Fixed defences protecting high-value assets often benefit from concealment. But patrol vehicles are, by design, meant to be seen. Their very presence—like a police jeep with a flashing beacon—can act as a deterrent to smugglers, handlers and local facilitators.

The platform exposes open, documented APIs for integration with other Indian C-UAS solutions and command-and-control frameworks.

The company expects that, over time, the Home Ministry and Defence Ministry will push for standardisation and unification of C-UAS systems across agencies to avoid fragmentation and accidental fratricide. Indrajaal positions itself as a platform player that is not only ready for that future, but actively advocating for interoperable, software-driven air security architectures.

With border drone incidents rising sharply, the discussion turned to scale: how many Rangers can be built quickly if forces decide to adopt them widely?

While the company did not publicly state a hard number, it affirmed that it is building the supply chain and assembly model for large-scale deployment, not niche boutique production. Partnerships with ecosystem manufacturers are being structured to support higher volumes if required.

On user response, Indrajaal pointed out that its wide-area autonomous systems (such as Ugrajal) are already deployed with the Indian Army and Indian Navy, protecting bases and high-value sites on both western and eastern fronts. These systems run 24×7 and have demonstrated real-world interception against hostile drones. Given that track record, the company believes border guarding forces, paramilitary units and police will be the fastest adopters of Ranger-type patrol systems, with more complex Army mechanised induction to follow as variant and integration work matures.

Regarding kinetic kills, the company clarified that in the Ranger configuration, interceptor drones are primarily used for pursuit and tracking, not always for kamikaze strikes. Knowing where a hostile drone lands can be as valuable as destroying it in the air because it exposes logistics chains, pickup points and handlers.

As for conventional munitions, Indrajaal is clear that in border villages, urban corridors and domestic airspace, it is neither practical nor responsible to rely on explosive munitions or high-energy weapons for every interception. Additionally, using an extremely expensive missile or interceptor against a cheap hobby-grade drone often fails the cost-exchange test.

Ranger is intentionally optimised for cost-effective, scalable defence against the most common class of threats: commercial and DIY drones used for smuggling and low-end attacks.

Looking ahead, the company confirmed ongoing R&D for naval and helicopter variants, but cautioned that these are more complex endeavours. Helicopters are easy targets, but hard to protect, owing to rotor dynamics, avionics, EMI and weapon integration constraints.

Any counter-drone system used in India’s internal security grid must pass through ARDTC (Anti Rogue Drone Technology Committee) under the Ministry of Home Affairs. Indrajaal stated that it has aligned its systems to these regulatory requirements and is ready to support national rollouts as frameworks mature.

As the interaction wrapped up at T-Hub, one point was unmistakable: Indrajaal Ranger is not just another gadget on wheels. It represents a shift in how India thinks about mobile airspace security—platform-first, autonomous, networkable, and designed for the messy, real-world mix of borders, villages, highways and urban sprawl. In an age where drones are being used to transport drugs, weapons and explosives across borders and into cities, Ranger aims to be the vehicle that quietly sits five kilometres away, detects threats at ten, and stops them before they ever reach Indian streets.

This is second in the series of reports ADU has filed after watching the launch live at Hyderabad.