- When Supply Chain Meets Strategy — Story of Innovation, Integration and Indian Ingenuity unfolds

- The Supply Chain Equation: Testing, Raw Materials, and Policy Synergy Define India’s Aerospace Future

- Amber Dubey’s Dynamic Moderation Lights Up the Supply Chain Panel at Aviation India 2025

By Sangeeta Saxena

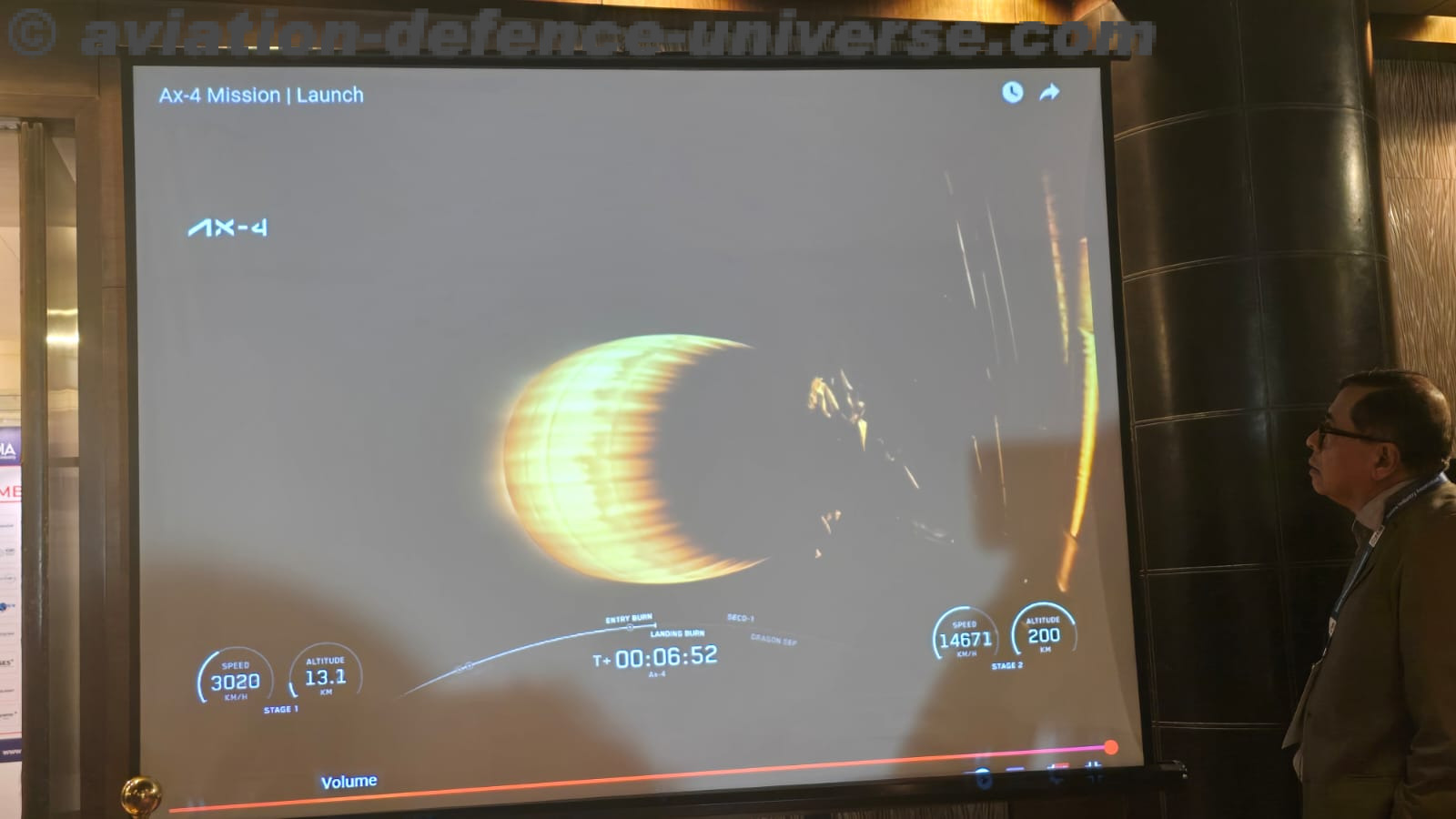

New Delhi. 03 November 2025. In a country where civil and defence aerospace ambitions are soaring, the question of how to strengthen India’s supply chain has become central to every industry conversation. The Aerospace Supply Chain session at Aviation India 2025 brought together thought leaders, innovators, and entrepreneurs who are shaping the next chapter of Indian aerospace manufacturing. Moderated by Amber Dubey Senior Advisor McKinsey & Company who has also done a three year tenure as Joint Secretary in the Ministry of Civil Aviation. He was one of nine domain experts hired by the Modi government in 2019 as ‘lateral entrants’ to the bureaucracy. The session saw frank discussions on the pain points of qualification, cost, design capability, testing infrastructure, and policy hurdles.

Setting the tone for the discussion, Ashwini Bhargava explained that aerospace manufacturing is not for the impatient. “For three years to qualify these kinds of parts, so you’ve got to start working ahead of time. If you are in the catch-up mode, I don’t think it’s going to work in that space,” he noted. For Indian suppliers aspiring to enter the global supply chain, the payback period is long and demanding. “It takes about a year for a supplier to get to that level of readiness. Then it takes about six or seven months for the RFP process to happen. Then it takes about two and a half years for qualification. So you should be prepared for a long haul, not a return to normal. It’s not like a one-night stand — it’s like a normal daily session and finally the bells will be tolled,” he quipped, drawing laughter from the audience.

One myth that the session effectively debunked was that OEMs prefer exclusivity. “A lot of people also feel that if I supply to Boeing, I have to be part of their clan. That’s a big myth,” said Bhargava. “In fact, what they told us in the beginning is that they actually want you to supply multiple players. They would never like a Boeing supplier to just stick to Boeing because it helps you meet ups and downs and demand curves.” He cited examples. “Dynamitics is healthy because they work with both Airbus and us. The defence business is more unpredictable, so we don’t want suppliers to be stuck with us and have 20 dead drops one day and none the next.”

The supply chain challenges in India’s aviation industry stem from a mix of structural, regulatory, and infrastructural limitations that hinder its global competitiveness. Despite the sector’s rapid growth, Indian manufacturers and MROs face persistent bottlenecks such as dependence on imported raw materials, long qualification timelines, and limited access to certified testing facilities for aerospace-grade components. The absence of a robust domestic ecosystem for specialised materials like composites, alloys, and avionics parts further increases costs and lead times. Moreover, fragmented supplier networks, complex licensing and export control procedures, and inconsistent policy implementation often delay production cycles and discourage MSME participation. While OEMs like Boeing and Airbus continue to expand local sourcing, the ecosystem still struggles with scale, certification, and design capability — the very ingredients needed to turn India from a low-cost assembly destination into a truly self-reliant aerospace manufacturing hub.

“We are in a business where any passenger would touch and feel what we make — seat parts, meal tables, sidearms — things that define the comfort of flying,” he explained ,“You may not notice them consciously, but they shape your flying experience. So ours is a very aesthetic and tactile business.” AeroChamp, he explained, began modestly, catering to the aftermarket with smaller parts, and gradually progressed toward becoming a supplier to major OEMs. Among its most significant innovations is the Aviation Foam— once fully imported, now designed and manufactured indigenously in India. “Until about 10 or 11 months ago, not a single aviation foam was being made in India — and now, there’s none being imported,” he shared proudly.

Discussing challenges, Dr. Srivastava highlighted the gaps in India’s testing ecosystem. “Testing and certification in aerospace are highly demanding,” he said. While he lauded the excellent facilities at NAL and HAL in Bengaluru, he pointed out the absence of a 16G dynamic testing facility, which forces companies like his to send components abroad for mandatory tests. “One single test can cost around $20,000, and if it fails, that money is lost,” he noted, adding that such costs and logistics strain small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Despite this, AeroChamp continues to push boundaries, focusing on domestic innovation. He emphasized the need for robust local testing infrastructure to make indigenous manufacturing truly sustainable.

On raw materials, he said, “When we started manufacturing meal tables, we were importing plastics from Europe and only thermoforming them here — the value addition was barely 50%, and it didn’t make business sense.” Collaborating with an Indian polymer manufacturer, AeroChamp successfully developed indigenous plastics that now comply with stringent Fire, Smoke, and Toxicity (FST) standards. “Every cabin component — cushion, lining, fabric, leather — must qualify these parameters, both individually and as a composite,” he explained. Achieving this milestone in India has shortened lead times, reduced costs, and strengthened self-reliance. Concluding the conversation, Dubey summed it up aptly: “AeroChamp is proving that Indian innovation isn’t just flying — it’s making the skies more Indian, one seat at a time.”

“In building our ecosystem, we actively went hunting for partners across industries,” he explained in response to an audience question. “We reached out to raw material manufacturers and processors, many of whom were originally catering to the automobile and industrial sectors. I told them upfront — my volumes are small, but I’m willing to invest my time and money with you in researching and developing the right materials. Work with us now, and it will pay off in the long run.” The approach proved successful. “We’ve since built a robust supply chain across India, with backend suppliers and vendors spread across Maharashtra, Delhi, Rajasthan, and Gujarat. It’s a truly pan-India network that’s helping us strengthen our manufacturing base and ensure reliability in every stage of production.”

Praising regulators for their evolving support, he added, “Let me thank DGCA. The Aircraft Engineering Department has very skilled and knowledgeable people. My company is probably one of the leading DOA and POA in India — and DGCA has done a fantastic job.”

India’s MSME sector forms the backbone of its aviation and aerospace supply chain, providing crucial support to both domestic and global OEMs. These small and medium enterprises supply a wide range of components — from precision-engineered parts, sheet metal fabrications, and composites to avionics subassemblies and interior fittings — that meet stringent international standards. Over the years, Indian MSMEs have demonstrated remarkable agility, quality, and cost-effectiveness, earning supplier certifications from giants like Boeing, Airbus, Safran, Rolls-Royce, and GE. Many of these enterprises have evolved from tier-3 vendors to trusted tier-1 and tier-2 suppliers, contributing to India’s growing role in global value chains. However, while their technical competence is undeniable, MSMEs still face challenges such as limited access to finance, technology upgrades, and certification infrastructure. With targeted government initiatives, offset opportunities, and OEM partnerships, India’s MSME network is steadily transforming into a powerful enabler of the country’s ambition to become a global aerospace manufacturing hub.

Speaking about government facilitation, he acknowledged progress but identified India’s stringent export control regime as a key constraint. “These controls were put in place to prevent sensitive technologies from reaching unfriendly nations, but the way they’re structured today, they affect everyone — even open-source technologies,” he said. “We make parts designed in collaboration with our global customers like Boeing or MCI, but since we don’t own the IP, the controls still restrict exports.”

He elaborated that the regulatory framework for aerospace exports is complex, governed jointly by the DGFT for civil aviation and the Ministry of Defence for defence-related items under the SOMED (Special Order for Military End Use). “Even if a product is civil in nature, we often need clearances from the defence side because it can be repurposed,” he explained, citing examples like logistics drones that could theoretically be converted for military use. “There is something called an Open General Export Licence that relaxes controls for very small, non-repurposable drones — typically those under 0.5 kilograms — but for everything else, it’s still extremely rigid.” His appeal to policymakers was clear and pragmatic: “Open-source technologies and parts for which Indian companies do not own the IP should be taken out from the purview of export controls. That single reform would remove a major bottleneck and help Indian aerospace manufacturers integrate more seamlessly into the global supply chain.”

The Aerospace Supply Chain panel at Aviation India 2025 painted an honest picture of the challenges — slow approvals, high testing costs, dependence on imported raw materials, export restrictions, and fragmented advocacy. Yet it also reflected a collective optimism — an understanding that India’s aerospace story is about patience, persistence, and partnership. From global giants like Boeing to innovators like AeroChamp and Lohia Aerospace, the message was unified: build design capability, indigenise raw materials and reform policies to empower the ecosystem. As the audience applauded, one sentiment echoed through the hall — the future of aerospace in India isn’t just in the air; it’s being built, tested and certified right here on the ground.

India’s aerospace manufacturing landscape is undoubtedly evolving — but the question remains: has “Make in India” truly taken flight in the supply chain? At Aviation India 2025, industry leaders from Boeing India, AeroChamp, and Lohia Aerospace acknowledged that while the spirit of self-reliance is strong, the runway ahead is still long. The consensus was clear: India’s aerospace dream is in the air, but to sustain its altitude, the supply chain must become deeper, more self-sufficient, and globally competitive.