- From Importer to Innovator: DRDO’s Blueprint for Tech-Led Self-Reliance

- Break the Barriers, Back the Builders: DRDO’s Plan to Outpace Disruption

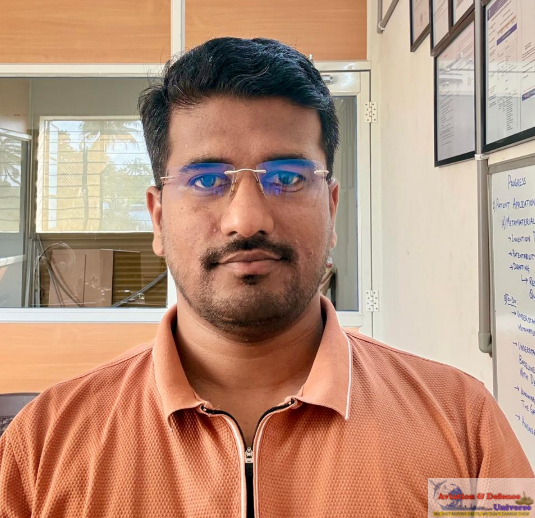

- Fail Fast, Field Faster: Dr. Samir V. Kamat on India’s Defence R&D Reset

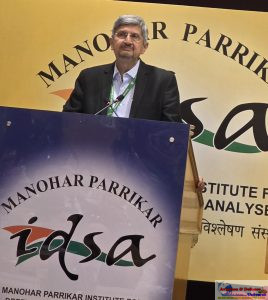

New Delhi. 13 November 2025. At the Delhi Defence Dialogue, Secretary DDR&D and DRDO Chairman Dr. Samir V. Kamat sketched an unambiguous path from import dependence to indigenous dominance stated , “if we have to win the battles of the future, we must transition to indigenous systems and indigenous capability. Dependence on foreign systems will not yield desired support during a conflict. The Russia–Ukraine conflict has shown that what works today may not work in 15–20 years. The pace of change in both offensive and defensive systems is so rapid that inherent capability is the only safeguard against obsolescence.”

DRDO is retooling its development pipeline around disruptive technologies whose civilian frontiers move faster than military acquisition: AI/ML, advanced communications, semiconductors, robotics, smart materials, quantum, directed energy. The new model places industry inside the tent from project start via DCPP (Development-cum-Production Partners)—now two partners selected competitively (PSU or private) for every mission-mode programme—so design absorption, upgrades, and production scaling begin early, and lab scientists are freed to chase next-gen leaps. An expanded TDF now bankrolls frontier research, not just indigenisation. Add co-R&D with like-minded nations (e.g., the BrahMos and MRSAM precedents) and hub-and-spoke Centres of Excellence across leading institutes with larger grants and clear domain missions, and the outcome is a shorter, sturdier bridge from lab to line—precisely what fast-cycling battlefields demand.

He continued, “We are also in an era where if we do not keep pace, we are going to be outdated by the time we decide and develop those technologies which are required. If you look at what has been happening in the country, we had a fairly syllogized system — DRDO doing R&D, industry doing mostly production, and academia doing their own R&D, whether or not it was relevant to our needs. As a result, till recent years, we were a major importer of weapon systems, with 60 to 70 percent of our systems, sensors, and platforms being imported. This is changing, and I am glad to say that last year, more than 90 percent of all orders placed were for Indian systems.”

“We have to break the silos that exist between organisations. We are too compartmentalised and must find ways to work seamlessly across institutions and utilise all national resources optimally. Yes, there are organisational and IT barriers, but we have no choice but to overcome them. We are already seeing this change, and I am confident that in the coming years, these silos will continue to break down. Within DRDO, we are aware of these challenges and have initiated reforms in line with the Ministry of Defence’s vision. One major step is that for every mission-mode system development project, we will now have two industry partners—called Development-cum-Production Partners (DCPPs)—chosen on a purely competitive basis. We make no distinction between the public and private sectors; both have equal opportunity once they meet the technical criteria. This ensures better technology absorption, faster production, and cost control, ” he explained.

DRDO’s push redefines Atmanirbhar Bharat from “build at home” to “innovate at speed and scale.” The ingredients are structural: two-partner co-development, bigger TDF cheques for cutting-edge (not only catch-up), Young Scientists’ Labs tasked with AI, quantum, smart materials, man-unmanned teaming, and mission-mode programmes that accept spiral development—field 80–90% solutions early, iterate to the last 10% in parallel. The cultural keystone is explicit: failure is an investment when it is fast, instrumented, and learned from. Blend this with international co-R&D, a growing defence-industry–academia triad, and a deliberate shift from net-centric to data-centric architectures, and Atmanirbharta becomes a repeatable engine—one that moves India from technology adoption to technology leadership.

“Technology dominance is ultimately a people strategy. Innovation thrives best in start-ups and MSMEs, which are driven by passion and agility rather than bureaucracy. We are therefore creating mechanisms to fund and support them, alongside reforms to encourage academia to contribute directly to national needs. We have established 15 Centres of Excellence in premier institutions under a hub-and-spoke model, bringing DRDO labs, academia, and industry together in defined domain areas. These centres will replicate the ecosystems that made Caltech, MIT, and Stanford global innovation hubs. Earlier, we funded small academic projects worth ₹50 lakh to ₹1 crore. Now, we are giving projects worth ₹50–70 crore to develop critical technologies. At lower TRLs, academia takes the lead; as we move up the chain, DRDO and industry play larger roles. This approach will accelerate technology development and reduce the gap between research and deployment, ” continued,” exclaimed Kamat.

Dr. Kamat’s message was clear: India cannot buy its way to overmatch; it must build it—faster than the threat evolves. That demands more R&D spend, less siloed work, opened IP, co-development from day one, bigger, bolder funds for frontier tech, and scientists trained and trusted to move fast. DRDO’s course correction turns a familiar triad—people, process, product—into a national play: train the people, free the process and field the product. The pudding, as he reminded the room, is in the eating—and Operation Sindoor showed India’s taste for home-grown game-changers has only just begun.