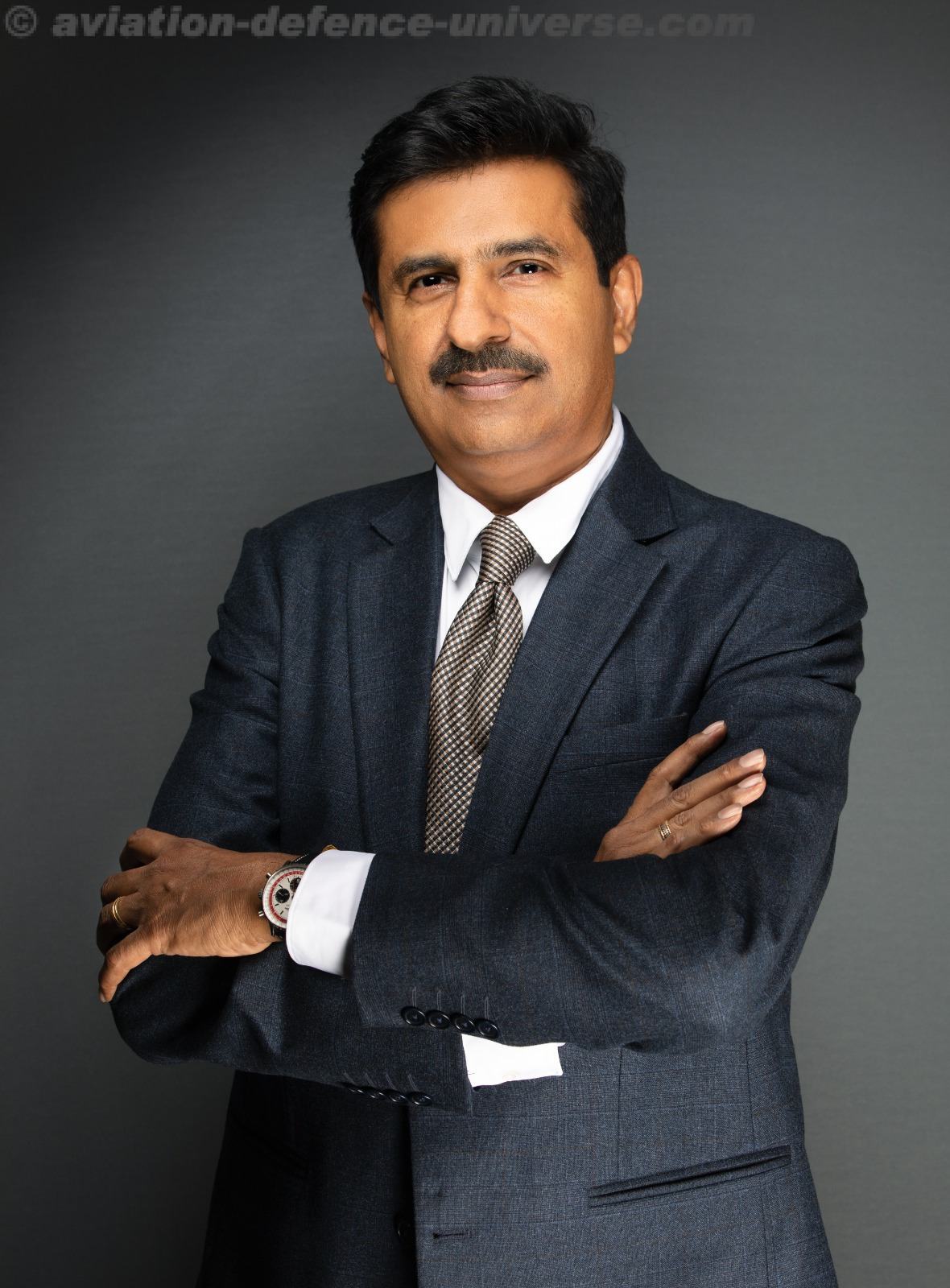

By Lt Gen Mukesh Sabharwal, PVSM, AVSM**, VSM (Retd.)

New Delhi. 15 April 2020. The other day a friend of mine asked me if I had ever served in Kashmir. He observed a bemused look on my face, so I told him why I was smiling. A quick look down memory lane and I recollected my half a dozen tenures in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), starting with participating in the 1971 Indo-Pak War as a Subaltern; to my Company Commander’s stint on the Pir Panjal Mountain Range in an eye-ball to eye-ball deployment on the Line of Control (LC); to commanding my Battalion in Ladakh and Siachen; to my participation in Operation Parakram; to commanding my Division on the Shamsabari Ridge along the LC; and finally having the privilege of serving as GOC 15 Corps. The last posting was indeed an honour and a most humbling experience as one saw the illustrious Rogues Gallery of the Chinar Corps.

One could reminisce for hours about events in various tenures, especially my last one in 2007-08. The onerous responsibility involved preserving the sanctity of the LC, counter infiltration and counter terrorist operations in the Kashmir Valley, as well as advise the State Government on all matters of security. Rather than narrating several incidents, I shall focus on a significant one during that period, pertaining to the Shri Amarnath Shrine Board agitation.

In early 2008, there was a general feeling all around that normalcy was returning to the Kashmir Valley. Violence levels were low, infiltration well in check, the line of control relatively quiet and the Muzzafarabad–Srinagar bus service operating smoothly. Other indicators of normalcy like the continuous tourist inflow into the Valley over the previous couple of years, the satisfactory pilgrim numbers for the Amarnath yatra, and encouraging trade figures further reinforced this belief. The Chief Minister had invited Mrs Sonia Gandhi to inaugurate the Tulip Gardens, a fresh initiative to lure tourists and open a new avenue of horticulture export. Despite the usual political under-currents, the State Government of Ghulam Nabi Azad appeared to be fairly stable in J&K. The situation however was too good to last and the gradual move towards normalcy received a setback, when the land transfer controversy sparked off widespread protests and agitations. Some analysts were convinced that it was a return to the nineties era, while others felt that it was a leaf out of the Arab Spring movement in the Middle East.

The Shri Amarnath Shrine Board (SASB) Agitation

The State Government’s approval on 20 May 2008 for transfer of 40 hectares of forest land to SASB triggered the land transfer controversy. The separatists led by the hardliner Hurriyat leader Syed Ali Shah Geelani and moderate Mirwaiz Umar Farooq declared that the land transfer order was an attack on Kashmiri identity aimed at demographic reorientation of the Valley. This led to large-scale protests demanding immediate revocation of the order forcing the State Government to relent and revoke the order. It was hailed as a triumph of street power in the Kashmir Valley, but the same order sparked violent protests in the Jammu region with political parties and interested groups whipping up religious and regional passions.

The land transfer order was in vogue since 2005 and the decision to create permanent facilities was not a sudden one; it was under process for some time. Another argument was the inefficacy of outsiders to come and settle in a forest-land, cut off due to snow for six months in a year. The land controversy acted as the accidental trigger that scored a goal against the run of play. It was cleverly exploited by the Hurriyat, which had been effectively marginalized prior to the agitation and was looking for political space to survive. The main regional political parties too tried to extract maximum political mileage in an election year. Vote bank politics overtook the wider national interest. Governor’s Rule was imposed in the State in July 2008 after the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) withdrew its support to the coalition government headed by the Congress. Meanwhile, Mr NN Vohra, a seasoned bureaucrat took over as the Governor of J&K from Gen SK Sinha.

The blocking of traffic on the NH1A affecting the upward and downward movement of supplies, although only for a few days, aroused widespread concern across the Valley with separatists labeling it as an economic blockade against the State. The economy of the Valley largely depends upon horticulture. The anger of fruit growers, whose produce could not be transported in time and some of it rotted as a result, was exploited by the Hurriyat to organize rallies such as the “Muzaffarabad Chalo.” This was a march planned to press their demand for an alternative market to sell their wares in Muzaffarabad (in POK) via Uri. The State Government made all out efforts to keep the NH1A open to traffic and trade but its insistence that there was no disruption whatsoever only exacerbated the situation. It was followed by mass rallies on one pretext or the other. The crowds were not spontaneous but were spurred by the separatists, even by coercion, intimidation and money power. The blockade actually made the people realize the vulnerability of their sole economic link, which even at the height of militancy had never been threatened.

Muzzafarabad Chalo

The call for “Muzaffarabad Chalo” was initiated by both factions of the Hurriyat Conference, supported by the PDP and tacitly endorsed by Lashkar-e-Toiba. The rally was obviously at the behest of the Traders Federation and Kashmir Fruit Growers’ Association. The questions that arise are: Was it necessary for the separatists and the PDP to carry out “Muzaffarabad Chalo”? Was such a march warranted when several hundred trucks, loaded with fresh fruit left the Valley during the same period for Jammu and markets beyond? The Government it is understood had made arrangements for a fleet of over 500 trucks for carrying fruit out of the Valley but there was not enough fruit, which could be loaded in even half of those trucks. These fruit growers and traders had never given a call anytime earlier for using the Muzaffarabad route when the Srinagar-Jammu highway got blocked for several weeks on account of weather disruptions. Why then the call this time? The call according to the detractors was to internationalise the Kashmir issue and was part of the plan of giving new thrust to the pro-Pak proxy war in the Valley. The call was also possibly given to influence Delhi to intervene so that effective measures were taken to keep the national highway open. Another aim was to neutralize the effect of the blockade enforced by the Shri Amarnath Sangharsh Samiti (SASS) spearheading the shrine land stir. It was quite evident that the Jammu protests came as a shot in the arm for the separatists who got an opportunity to polarize the Kashmiris by portraying the land transfer row as a “Kashmir versus India” issue.

The “Muzzafarabad Chalo” march on 11 August 2008 gathered momentum by mid-day as people in trucks and buses from Srinagar joined the protestors at Pattan and Baramulla, enroute to Rampur and Uri. I was on a visit to my formations in South Kashmir when my BGS contacted me from Srinagar and informed me that the Governor was rather worried about the situation and was anxious to meet me, which was understandable. I decided to fly to Baramulla and assess the ground situation for myself. While overflying the national highway Srinagar – Baramulla, I observed large crowds, especially from Pattan onwards. People were travelling in all modes of transport, including buses, trucks and hundreds of pedestrians. I picked up Gen Ata Hasnain, GOC 19 Div at Baramulla and we flew to the Rampur helipad. The administration and police were unprepared and had not anticipated the anger and determination of the people. The numbers reported were grossly exaggerated and varied between 70,000 in the national news to even 250,000 in the Dawn newspaper of Pakistan. The actual figure of the crowd that crossed Baramulla and reached Sheeri, a few kilometres ahead was approximately 25,000 to 30,000 at best, as we could fairly accurately estimate the strength of the vehicles and people on the roads. Measures for crowd control by the local police were conspicuous by their absence despite intelligence inputs available well in time. We directed the local units to assist the state police and CRPF troops to block any further move beyond Rampur. But for the timely assistance by the Army at Rampur and Uri, the situation could have spiraled out of control. The police managed to halt the protestors short of Buniyar but by then the damage had been done. Five people died in the firing including Sheikh Abdul Aziz, one of the leaders of the Hurriyat.

We realized that the job had only been half done. The next critical point was Uri. The stretch from Rampur to Uri had its own set of supporters who were willing to cross over to Muzzafarabad over the Kaman Bridge located on the LC. So we flew in the helicopter to Uri next and instructed the formation to seal the routes at the appropriate places. For me, the sanctity of the LC was paramount and it had to be protected at all costs. I vividly remember speaking with the Governor from Uri in the afternoon. He was surprised and wondered what I was doing in Uri. He was however relieved when I reported my assessment of the situation and assured him that there would neither be any trouble beyond Rampur nor on the LC ahead of Uri. There was no doubt in either of our minds though, that further such agitations were around the corner and we should be prepared for stiffer challenges in the coming days.

Following the police firing on August 11, the separatists in Kashmir region organized several protests in the following weeks. 15 civilians got killed during the protests and in the resultant firing by police and paramilitary forces. More than a 100 people were also injured in a dozen separate incidents across the Valley. On August 31, 2008, the 61-day old agitation over the Amarnath land row in the Jammu region ended, following the signing of an agreement between the group leading the agitation and the panel appointed by the Governor. Under the terms of the agreement the Shrine Board could make temporary use of 40-hectares of land during the relevant yatra period.

The agitation both in Kashmir and Jammu regions was a case of gross political opportunism in the election year. The separatists succeeded in fanning the embers of a gradually receding insurgency movement thereby helping the terrorist cause. This one issue almost resulted in reviving the latent sentiments of regionalism, communalism and separatism in the State. The J&K Police and CRPF effectively handled the agitation without the direct involvement of the Army. Restrained firing, when absolutely necessary, was resorted to. Inadequate training and a lack of motivation were considered to be the general causes of police ineffectiveness but it shouldn’t be forgotten that requisite and appropriate equipment to control crowds by the police was conspicuous by its absence. The J&K Police faces a peculiar psychological and motivational problem while dealing with mass agitations in the Valley. The local police come from the same stock as the masses and obviously sympathise with the crowds carrying out the agitations. The police may also face the hazard of reprisals against their families by the masses and terrorists. Secondly, a switch to uncomfortable duties like handling non-violent mass protests has not been an easy one, but the police and CRPF have generally conducted themselves with utmost restraint and patience even at the cost of their humiliation when they have to see protestors burning Indian flags and taunting them. The State Police and CAPFs should continue to be accorded due recognition and primacy, besides upgrading their capabilities to retain their effectiveness in managing law and order situations.

Some months later, the State Assembly elections in Nov-Dec 2008 were an unqualified success despite many security analysts and doubters in the Central government having their reservations. With an elected government in place, the Governor’s rule ceased to exist, the Governor Mr NN Vohra having handled the situation very competently like an astute professional.

The Amarnath yatra has been progressing smoothly ever since, with numbers and the duration of the pilgrimage varying every couple of years based on the terrorist threat and the overall security situation. The Yatra however was disrupted abruptly in August 2019 when Article 370 of the Indian Constitution was revoked by the Parliament.

On reflection, this was one of the poignant events of my tenure as Corps Commander, not counting the many operational challenges of course. All commanders and troops of the Chinar Corps rose to the occasion every time and exhibited exceptional courage and devotion to duty. The security forces functioning under the directions of the Core Group of the Unified Headquarters in the Kashmir Valley learnt many a lesson in handling mass protests. This was to come in very handy in the subsequent years when the frequency of such agitations increased manifold.

For the next three years, I moved to New Delhi as the Adjutant General, which too was a very absorbing assignment and had its own share of challenges that affected the entire Indian Army. However, very often I missed the excitement and freshness of Kashmir.

The author Lt Gen Mukesh Sabharwal PVSM, AVSM**, VSM (Retd.) was former 15 Corps Commander, Srinagar , J&K and Adjutant General, Indian Army. The views in the article are solely the author’s. He can be contacted at editor.adu@gmail.com