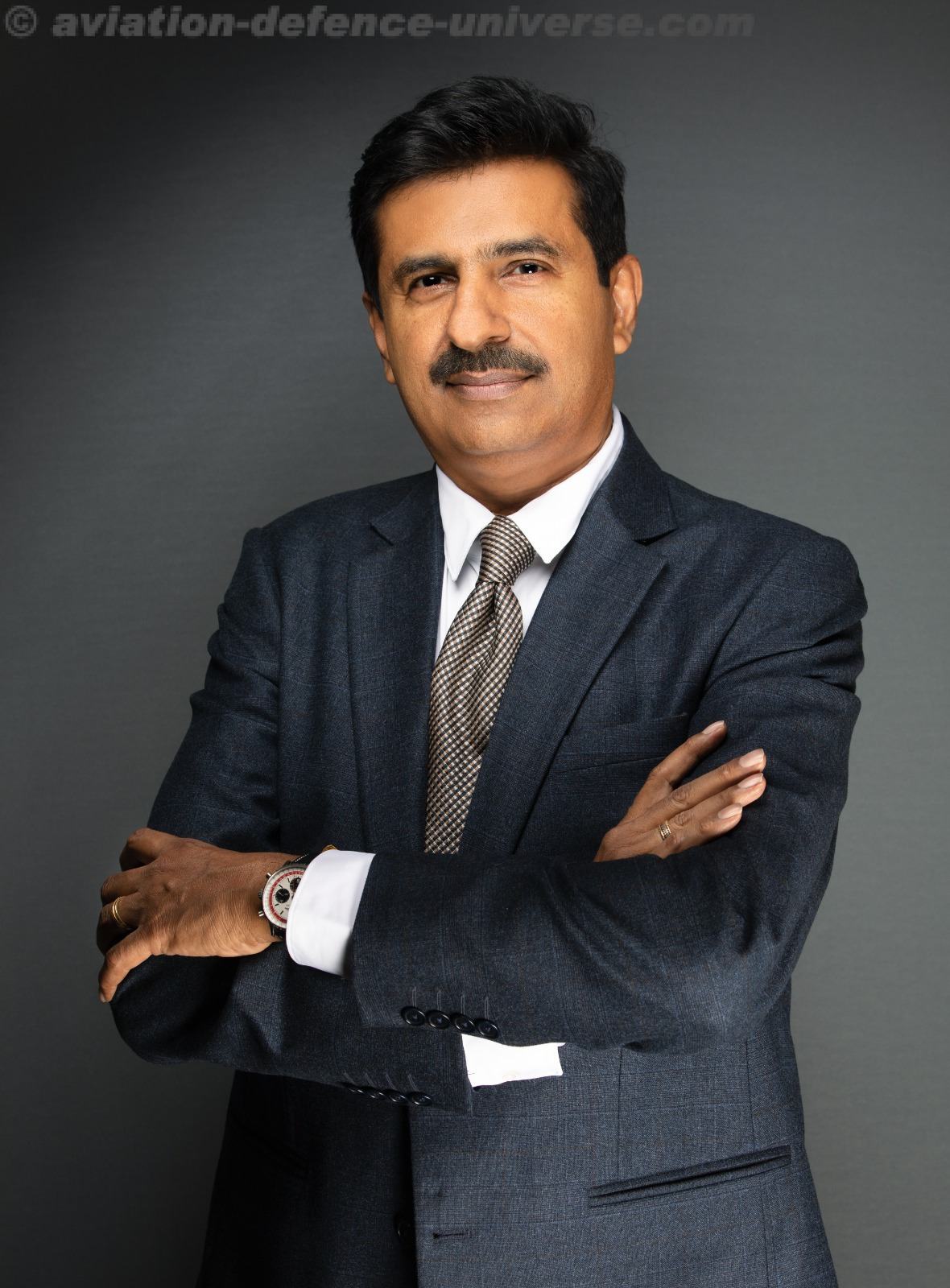

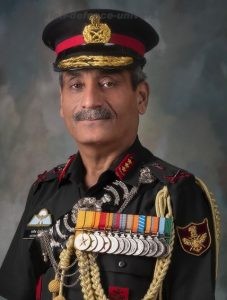

By Lt Gen Satish Dua, PVSM, UYSM, SM, VSM (Retd.)

New Delhi. This is the story of an army officer who learnt how to gather intelligence about terrorists in real time, to plan counter terrorist operations in a manner that innocent bystanders don’t get hurt, to lead troops boldly, to take decisions even when there were no clear directions on dealing with tricky situations, to deal with emotions personally and to hide one’s own fears. This is my story.

I was promoted to the rank of a Colonel in 1998 and I was appointed as the Commanding Officer of my own Battalion, 8 JAK LI (Siachen) which has the official honour of ‘Bravest of Brave’. Our unit had moved from Port Blair to the Line of Control (LoC) in J&K just a month ago. Our Area of Responsibility (AOR) just south of Pir Panjal Ranges (PPR) was operationally very active. When we reached our AOR the focus of infiltration was shifting to South of the PPR, since the counter infiltration grid had become very strong in the Kashmir Valley. Every Infantry officer aspires to command the unit he was commissioned in, and hopes to get an opportunity to lead his soldiers in combat. I was fortunate to get both in the summer of 98. God was more than kind, he threw in a bonus too. I assumed command of my battalion in the area where we were raised as a volunteer force fifty years ago (yes, it was the golden jubilee year), and we were occupying the very same forward posts on the LoC that our soldier-forefathers had established in 1948, during the First Indo Pak war. How much luckier could a man get? It was a-dream-come true for me.

Counter terrorism is the trickiest operation; it is like playing chess with live bullets. A soldier is trained to fight an enemy, to fight for his country, to fight the enemy to ensure his country is not invaded. But what do you do in a situation where there is no clear distinction between friends and foe, where there is no border to be defended.

Within the one week, we had our first encounter with terrorists. And I lost an officer, Major Rohit Sharma, SC (Posth). It was such a blow that euphoria of promotion and becoming the CO of my own battalion evaporated even before it had sunk in well enough. Here, I must pause to explain that our previous operational experience had been in Operation RHINO in Assam, where the terrorists had mostly handguns, had lesser ammunition comparatively speaking – both in quantity and lethality, and their own training standards were rudimentary. In J&K, the terrorists were better equipped, more motivated and the foreign terrorist element were operationally experienced and many of they were combat-hardy since they had operated in Afghanistan in the past. We taught all of this to our soldiers during our pre induction training. However, it sank in with a jolt after the loss of Major Rohit Sharma, SC (Posth). The morale of the unit was shattered; even I could not sleep that night.

It was then that I realized that my soldiers were looking up to me for leadership. So, I gathered myself and addressed the boys the next morning. “Yesterday, we lost a brave officer who took a bullet in his chest while leading from the front. Today, as we grieve his loss, what is the best way to pay homage to such a martyr? By eliminating more and more terrorists! Our battalion has such a rich history of gallantry in all operations since independence. Look at what we did in Siachen? There too, our first operational casualty was an officer, and look how we covered ourselves with glory by executing the highest successful attack in the world, one PVC, one MVC and a very long list of gallantry awards. We are going to do just that! Pay homage by ensuring that not a single terrorist remains alive in our AOR.”

Little did I know then that my world would turn out to be prophetic and we went on to neutralise 106 terrorists/enemy, which is a record of sorts on the LoC. I remember in the second encounter that we had, I didn’t wear bullet proof jacket- I was acting braver than I felt. Foolish as it may be, my taking this risk and leading from front really inspired the soldiers. During the encounter, I saw a very different kind of energy in my troops. That set the trend, there was no stopping the young officers, and even soldiers. All of them wanted to outdo each other during operations. Whenever an encounter ensued, we also had to pool those at the Battalion Base to provide reinforcements or stops etc. We always had more volunteers than we needed. I have had a cook asking to be taken along to participate in an operation. On another occasion a driver who was taking reinforcements to the encounter site, abandoned his vehicle at the road head and accompanied the soldiers into combat! All these incidents and more set up such a positive cycle of bravery. Whenever I think of my soldiers, it strikes me that Indian soldier asks for so little, but is ready to sacrifice his life without even asking why? The charge of the light brigade…Some of them were mere teenagers.

My unit had an unusual number of young soldiers. Over fifty percent of the boys had less than five years’ service, with practically no operational experience. How did this happen? At the National level it was decided to recruit additional youth from J&K, to wean them away from militancy. Since JAKLI is the only Regiment that has soldiers only from J&K state, it was decided to raise five new battalions in three years. This was additional strain was on older units like mine, as we had to send experienced soldiers to new units to get those units going, and absorb a disproportionately high share of young soldiers in return. While most COs lament the lack of experience when they get inducted into operational areas, I decided to see this as an advantage (eternal optimist that I am…) and used to joke that in our golden Jubilee year, we are a young battalion with a young CO. But jokes apart, we tweaked the organisational structure to suit operational realities. The more experienced soldiers were deployed on LoC posts, and younger, fitter soldiers were grouped under young officers into small teams in mission mode, to patrol in the tough terrain and harsh climate and ambush the infiltrating terrorists. This tweaking paid rich dividends, and we reaped great operational successes.

When I look back, I also recall that in those days, there was no LC fence to stop infiltration, no sophisticated thermal night vision devices, the bullet proof jackets were so heavy that despite being a life saver, several soldiers had to be checked for chucking it away, since the weight of the jackets slowed them down considerably. The technical intelligence was much lesser; reliance was more on human intelligence, better known by its snazzier name, Humint. Oh, there was surfeit of that; there were professional sources all over. These sources, who had been around for long, were of limited value as far as actionable intelligence was concerned. True, they were a storehouse of background information, and could lead you to caches when put under extreme pressure. The country side was full of ammunition caches buried in the mountains by from some infiltrating group in the yesteryears. Whenever anyone needed a favor from the army they would lead one to one of these caches. So, for our operations we really had to depend on our resourcefulness, on cultivating of new sources and on the Josh displayed by the junior leaders.

So all in all, counter terrorism milieu is a fuzzy environment to say the least, and it requires a great deal of ingenuity and innovativeness on the part of a counter-terrorist, if I may use the term. Counter terrorism operations are really a company commander’s battle. A Commanding Officer can be a reassuring support, provide reinforcements and logistic backups. But, there is one very important role that a commanding officer plays which makes the difference between success and failure, between Josh and ‘issue-type’. And that is, his support and guidance, timely decisions, shoulders broad enough not to let any pressure pass down, and positive strokes to soldiers. If he does all of these, his command WILL do well. And if he can drink rum with soldiers and dance with them on occasions, they will carry him on their shoulders, in all senses of the word.

So how does a commanding officer take firm decisions, even when he doesn’t get clear directives? For instance, dominating the LoC aggressively calls for a lot of initiative in the absence of clear cut SOPs as to what all it can encompass. Here steps in a great quality that separates the men from boys. Tolerance for ambiguity. I’ve been using this as an ethos amongst my subordinate commanders at all levels beyond a CO. If everything has to be given to a commander in black and white, then it’s a clerical approach. There lies the difference between a company commander and a commanding officer, and beyond. Command is a lonely responsibility. There isn’t always time to share the reasons for your decisions. You must seek advice from all, be democratic till the decision is arrived at, but thereafter make sure the decision is executed with a sense of ownership by all.

Commanding officers are the bulwark of Indian Army. It is the stage where you come into your own. Field Marshal WJ Slim starts his book ‘Defeat Into Victory’ by saying that the command of a battalion is the best command in the life of an army officer. On one hand a CO has operational freedom to plan his ops, and on the other hand, he is rooted to the ground – he still knows every soldier by name. Thus, quite justifiably, the commanding officer is also the most powerful man in terms of legal powers he is entrusted with.

Counter terrorism operations defy set formats. Each situation will be different, and a lot will depend on the quick thinking of junior leaders.

Such ops can succeed only if you’re emotionally involved. One option is an easy to do routine patrolling or ambush, while remaining out of harm’s way. When I became a Corps Commander in Kashmir a decade and a half later, few soldiers had been taken to task for some grievous consequences of an operational collateral damage, and several Company Operating Base (COB) commanders of Rashtriya Rifles (RR) were doing just that. I had to go around and ginger them up, assuring them of my support if there was an error while prosecuting operations in good faith.

Counter terrorism operations succeed only when those prosecuting them are passionate about their job, to the extent of getting emotionally involved. If not, then one can only hope for accidental success, but run the risk of own casualties. For the fully involved officers, own casualties act as rallying points, serve as pegs to turn the flow in their own favour. But there are a couple of other aspects of own casualties which merits mention. First, unlike war, I would rather let a terrorist escape than a soldier die. The escaped terrorist has a shelf life, and will be neutralised soon, by another unit if not yours. War is different. Integrity of borders has to be defended at all costs, on last man last round basis, if need be. Another aspect of casualties is the moral responsibility of a commanding officer, an unenviable part of his duties, is to break the sad news to the family.

Traditionally, in Indian Army, the CO breaks the news to the family in case of officers and Subedar Major does it for soldiers. It is one of the toughest tasks I have performed. Anyone who has never done it can never say, ‘Oh I know how tough it must be’ because you can’t know it unless you’ve done it. Allow me to narrate one such incident. On 17 June 2000, in an encounter with terrorists near the LoC, we lost Major Pradeep Tathawade, my Second in Command, who died fighting bravely in a hand to hand combat. After the operation was over, and after I had ensured completion of all tactical searches, counting of bodies, weapons/ammunition/ equipment captured, quick debrief of all parties,

I then started walked up the thickly wooded mountain track for an hour to the nearest road head, from where my Gypsy took me to Poonch town in two hours. I did not even stop at my Battalion HQ enroute. I kept planning and forming words, on what is the best way to break the news. Can there be a best way for such a bad news? I went to a PCO Booth and placed a call to Mrs Leenata Tathawade. “Hello Colonel Dua’, she said chirpily. That made my job even more difficult. How do you tell her that that her husband’s body will arrive tomorrow and she should prepare for cremation. When I finally managed to tell her that there was an encounter — “Is he alright?” she interrupted — ‘in which Pradeep fought bravely and – ” I’m continuing, she shrieks again, “He’s no more, na?” Suddenly, my shoulders sagged, all at once I felt as if a load had been lifted off my shoulders. When I confirmed, she wailed, “Aayeee, aapne unko kyon bheja?” (Oh God, why did you have to send him for the operation?) The load had suddenly been placed on my chest. I was finding it hard to breathe, and it was not due to the small size of PCO booth. Her shriek, her wail will remain with me forever. She was not in a position to talk anymore thereafter. Frankly, nor was I, as I was also dealing with my own grief of having lost a friend and a colleague of nearly two decades, which had taken a backseat to breaking the news.

This reminds me of another incident. Just before I retired, in a public forum, I was asked as to what was my biggest achievement in my career. While I had never given it thought earlier, but rather than the surgical strike or operational successes, personal awards and achievements, promotions and placements, I replied that the biggest satisfaction for me was the remarriages I accomplished of the two widows of my boys who died in operations when I was commanding my unit, one of an officer and the other of a soldier. Nothing can give greater joy, as you really feel like a head of family in all respects, when you are the Commanding Officer in counter terrorism operations.

Those three years in command of brave soldiers in counter terrorism operations taught me life lessons, taught me tactics, taught me empathy, made me callous-ruthless, made me emotionally-sensitive, made me put a lot of confidence in my soldiers and faith in God, put much to store by power of positive thinking, made me capable that in times of some ambiguity, I could take a leap of faith and aim high. My officers, my soldiers and my gut instincts never let me down. Such grounding and grooming by my mentors, gave me strength to be in the counter terrorism milieu in all my commands at every rank, raise a new counter terrorism force in the Northeast as a Major General. Later, as a Corps Commander, when we were struck by a dark tragedy at Uri, we decided to, for the first time, to make the enemy also feel the pain, and launched an audacious operation, that came to be known as the Surgical Strike. It changed the way we respond and India finally shed the soft state tag.

Lt Gen Satish Dua, PVSM, UYSM, SM, VSM retired as the Chief of Integrated Defence Staff. He was the Corps Commander in Srinagar who planned and executed the Surgical Strikes in Kashmir. A counter terrorism specialist, who has commanded his Battalion and Brigade on LoC in J&K and raised a Division of Assam RIfles as a Maj Gen, called IGAR (East). The views are his. He can be contacted at editor.adu@gmail.com