- “Who Pays, Who Produces, Who Benefits?”

- Industry Leaders Push for Policy, Partnership & Production in SAF

- From Feedstock to Future Fuel: Experts Decode India’s Path to Sustainable Aviation

- Costs, Capacity & Commitment: Aviation India 2025 Concludes with Defining SAF Roadmap Dialogue

By Sangeeta Saxena

New Delhi. 06 November 2025. Achieving carbon neutrality and ensuring cleaner skies are no longer aspirational goals—they are essential commitments we owe to future generations. As global aviation continues to grow, the sector’s responsibility to reduce its environmental footprint becomes even more pressing. Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) stands at the heart of this transformation, offering a viable, scalable pathway to cut lifecycle emissions by up to 80% and support a cleaner, more sustainable aviation ecosystem. Investing in SAF, expanding its production pathways, and fostering collaborative policies across governments, airlines, and industry partners will allow us to decarbonise aviation without compromising connectivity or economic growth. Clean skies are a legacy we must consciously build—so that our children inherit a world where progress does not come at the cost of the planet, and where innovation and environmental responsibility move hand in hand.

The final session of Aviation India 2025 was arguably one of its most consequential. Focused on the roadmap for Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) in India, the discussion brought together influential voices from across the sustainability, aviation, energy, and finance ecosystems. Moderated by Vasudevan Sundramurthy, Head of Aviation, Travel & Tourism India/APAC at ICF International Inc., the panel brought forward an urgent message: India’s aviation decarbonisation journey cannot be delayed any further. As Dr. Nilay Ranjan summed up, “Sustainability is an important element that we measure ourselves in terms of intensity and how that’s moving-this is central to our whole strategy.” The session captured both the scale of the challenge and the optimism that well-designed policy, industry partnership, and technology adoption could define India’s global leadership in SAF.

The final session of Aviation India 2025 was arguably one of its most consequential. Focused on the roadmap for Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) in India, the discussion brought together influential voices from across the sustainability, aviation, energy, and finance ecosystems. Moderated by Vasudevan Sundramurthy, Head of Aviation, Travel & Tourism India/APAC at ICF International Inc., the panel brought forward an urgent message: India’s aviation decarbonisation journey cannot be delayed any further. As Dr. Nilay Ranjan summed up, “Sustainability is an important element that we measure ourselves in terms of intensity and how that’s moving-this is central to our whole strategy.” The session captured both the scale of the challenge and the optimism that well-designed policy, industry partnership, and technology adoption could define India’s global leadership in SAF.

From the very outset, Vasudevan underscored a fundamental truth: SAF is no longer a conceptual debate but a structural necessity. He reminded the audience that offsets may have “bought time” but have not changed the core problem—aviation still runs on conventional fuel. The conversation around SAF, he argued, has shifted globally from reporting emissions to transforming the entire fuel system. India, panellists agreed, must match this global shift with clarity and commitment. Vasudevan urged policymakers to take decisive steps, noting that “it’s about time that the Ministry of Civil Aviation steps up and announces something concrete in terms of what producers and customers can expect.”

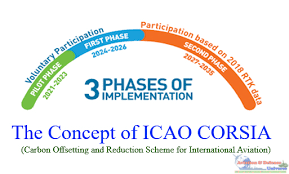

The International Civil Aviation Organization’s CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation) is the first global market-based mechanism designed to cap CO₂ emissions from international aviation at 2020 levels. Under CORSIA, airlines must monitor, report, and offset any emissions growth beyond this baseline by purchasing eligible carbon credits or using certified Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF). Since its adoption in 2016, CORSIA has been accepted by most of the world as a pragmatic first step toward aviation decarbonisation, with over 120 countries voluntarily participating in its pilot and first phases. While major aviation markets—including the EU, US, UK, Gulf nations, and many Asia-Pacific states—have integrated CORSIA into their regulatory frameworks, some developing nations have expressed concerns about economic impact and equity. Despite debates on credit quality, baseline adjustments, and the ambition gap, CORSIA has gained broad acceptance as a globally harmonised mechanism that avoids fragmented national regulations, stabilises international aviation’s climate impact, and provides a structured pathway toward deeper decarbonisation through SAF adoption and long-term net-zero goals.

The International Civil Aviation Organization’s CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation) is the first global market-based mechanism designed to cap CO₂ emissions from international aviation at 2020 levels. Under CORSIA, airlines must monitor, report, and offset any emissions growth beyond this baseline by purchasing eligible carbon credits or using certified Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF). Since its adoption in 2016, CORSIA has been accepted by most of the world as a pragmatic first step toward aviation decarbonisation, with over 120 countries voluntarily participating in its pilot and first phases. While major aviation markets—including the EU, US, UK, Gulf nations, and many Asia-Pacific states—have integrated CORSIA into their regulatory frameworks, some developing nations have expressed concerns about economic impact and equity. Despite debates on credit quality, baseline adjustments, and the ambition gap, CORSIA has gained broad acceptance as a globally harmonised mechanism that avoids fragmented national regulations, stabilises international aviation’s climate impact, and provides a structured pathway toward deeper decarbonisation through SAF adoption and long-term net-zero goals.

India has made its position on CORSIA clear: while it will not join the voluntary phases (2021–2023 and 2024–2026), it will participate fully when the mandatory phase begins in 2027, as required of all ICAO member states. In preparation for this obligation, India has already begun strengthening its aviation-sector readiness by supporting the development and adoption of Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), promoting 100% green energy usage across airports, and encouraging domestic firms to generate CORSIA-compliant carbon credits. This calibrated approach allows India to uphold its developmental priorities while ensuring it is fully prepared to meet the compliance requirements of the global carbon-offsetting regime when they become binding.

Mehnaz Ansari of Aerostrategix expanded this perspective to the everyday reality of India’s air quality crisis. She reminded the audience that sustainability is no longer abstract. “This is touching every individual… this is really impacting the people,” she stressed, citing recent efforts to induce artificial rainfall in Delhi and how flights themselves were affected by pollution. Her argument was clear: SAF is not just an industry obligation—it is a public health imperative. She emphasised cross-sector collaboration between energy and aviation, explaining, “The crosswalk is very important… sustainability is also responsibility of the companies which are in the market.” For her, India’s approach must encompass both environmental benefits and broader sustainability themes like employment equity and resource efficiency.

Mehnaz Ansari of Aerostrategix expanded this perspective to the everyday reality of India’s air quality crisis. She reminded the audience that sustainability is no longer abstract. “This is touching every individual… this is really impacting the people,” she stressed, citing recent efforts to induce artificial rainfall in Delhi and how flights themselves were affected by pollution. Her argument was clear: SAF is not just an industry obligation—it is a public health imperative. She emphasised cross-sector collaboration between energy and aviation, explaining, “The crosswalk is very important… sustainability is also responsibility of the companies which are in the market.” For her, India’s approach must encompass both environmental benefits and broader sustainability themes like employment equity and resource efficiency.

A major pillar of the discussion centred on economics—particularly the staggering cost differential between SAF and conventional fuel. Vasudevan pointed out that “offsets today are much cheaper than SAF certificates… the differential is one is to two hundred.” This gulf makes mass adoption financially unviable for airlines without policy support or incentives.

Rohit Kumar, Secretary General of CMAI & SAF Association, explained why the association was formed: to catalyse an industry-wide movement in a sector that cannot decarbonise without collective action. “We realised aviation is facing a big challenge… so we launched SAF Association,” he said. The goal, he stressed, is “not focusing on India market, but exploring global opportunities” and positioning India as a future hub of sustainable fuel.

He highlighted India’s enormous biomass potential—“50 million tonnes of agriculture and forestry waste”—and argued that SAF can lift farmer income by 10–15%. Rohit also emphasised that global players want to invest, but India must first create the right ecosystem. “Private players came to India… but shifted to other countries because they are not getting such an ecosystem,” he warned. This led to a crucial point: without a strong, predictable policy framework—similar to EU mandates or U.S. IRA incentives—producers cannot invest, and airlines cannot plan for SAF adoption.

He highlighted India’s enormous biomass potential—“50 million tonnes of agriculture and forestry waste”—and argued that SAF can lift farmer income by 10–15%. Rohit also emphasised that global players want to invest, but India must first create the right ecosystem. “Private players came to India… but shifted to other countries because they are not getting such an ecosystem,” he warned. This led to a crucial point: without a strong, predictable policy framework—similar to EU mandates or U.S. IRA incentives—producers cannot invest, and airlines cannot plan for SAF adoption.

Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) is produced through multiple certified technological pathways, each defined by its feedstock sources and conversion processes. Broadly, SAF can be categorised into bio-based and synthetic (power-to-liquid) fuels. Bio-based SAF includes pathways such as HEFA (Hydroprocessed Esters and Fatty Acids), the most commercially mature technology, which uses used cooking oil, animal fats, and vegetable oils. FT-SPK (Fischer–Tropsch Synthetic Paraffinic Kerosene) converts agricultural residues, municipal solid waste, and forestry biomass into fuel via gasification and synthesis. ATJ (Alcohol-to-Jet) produces SAF from ethanol or isobutanol derived from sugarcane, grains, or cellulosic biomass. Emerging pathways include CHJ (Catalytic Hydrothermolysis Jet) and HFS-SIP (Hydroprocessed Fermented Sugars). On the synthetic side, e-SAF or Power-to-Liquid SAF is generated by combining green hydrogen with captured CO₂—an option with high decarbonisation potential but still at pilot scale. Each SAF type varies in cost, scalability, and carbon reduction potential, but all meet stringent ASTM D7566 standards ensuring they blend seamlessly with conventional Jet A-1 to power commercial aircraft safely.

Aviation fuel markets are notoriously complex, and SAF is no exception. Dr. Nilay Ranjan noted that while IATA supports all SAF pathways, “0.7% of global demand is minuscule… a market failure.” His message was blunt: technology neutrality and production diversification are essential for driving down prices. Yet feedstock cost remains a major barrier—“You cannot keep adding the feedstock cost and expect airlines to pick it up, that is business unbuyable. The availability and consistency of feedstock, coupled with technological constraints across different SAF pathways, further complicate scaling. Airlines also face operational uncertainties, as SAF supply chains, storage systems, and fuel-blending logistics remain underdeveloped in many regions. Adding to this is the absence of clear, stable policy frameworks in countries like India, where mandates, incentives, and long-term procurement models are still evolving. Together, these challenges make SAF adoption promising yet difficult, requiring coordinated action across government, fuel producers, financiers, and the aviation industry for meaningful progress.”

Aviation fuel markets are notoriously complex, and SAF is no exception. Dr. Nilay Ranjan noted that while IATA supports all SAF pathways, “0.7% of global demand is minuscule… a market failure.” His message was blunt: technology neutrality and production diversification are essential for driving down prices. Yet feedstock cost remains a major barrier—“You cannot keep adding the feedstock cost and expect airlines to pick it up, that is business unbuyable. The availability and consistency of feedstock, coupled with technological constraints across different SAF pathways, further complicate scaling. Airlines also face operational uncertainties, as SAF supply chains, storage systems, and fuel-blending logistics remain underdeveloped in many regions. Adding to this is the absence of clear, stable policy frameworks in countries like India, where mandates, incentives, and long-term procurement models are still evolving. Together, these challenges make SAF adoption promising yet difficult, requiring coordinated action across government, fuel producers, financiers, and the aviation industry for meaningful progress.”

Tuhin Sen representing IATA explained, “SAF platform becomes so important—it brings producers, buyers and stakeholders together to discover market fundamentals and reduce existing asymmetries. We urge governments to participate more actively because a healthy ecosystem will incentivise greater SAF production in the country. We also realised that older technology aircraft would fall out of favour not only because of the expected drop in demand by 2040, but because certain policymakers, especially in Europe, hold strong views against airlines operating older technology aircraft or failing to retrofit. That concern really pushed us to analyse the sustainability-related policy impact on aircraft value, which is how this entire discussion began.”

Tuhin Sen representing IATA explained, “SAF platform becomes so important—it brings producers, buyers and stakeholders together to discover market fundamentals and reduce existing asymmetries. We urge governments to participate more actively because a healthy ecosystem will incentivise greater SAF production in the country. We also realised that older technology aircraft would fall out of favour not only because of the expected drop in demand by 2040, but because certain policymakers, especially in Europe, hold strong views against airlines operating older technology aircraft or failing to retrofit. That concern really pushed us to analyse the sustainability-related policy impact on aircraft value, which is how this entire discussion began.”

This is the time to be optimistic but the challenges faced in adoption of SAF cannot be ignored. The transition to Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF) by commercial airlines faces a series of interlinked challenges that hinder large-scale deployment despite its strong potential for decarbonising aviation. The foremost barrier is cost, with SAF currently priced at two to three times the cost of conventional jet fuel, making it difficult for airlines—already operating on thin margins—to absorb or pass on the increase to consumers without impacting profitability. Limited production capacity is another major constraint: global SAF output accounts for less than 1 percent of aviation fuel demand, leaving airlines without the supply volumes required for regular operations.

Mukund Santhanam, India Lead at Airborne Capital, brought the asset management perspective, explaining how sustainability concerns are already affecting aircraft values globally. As a lessor, he emphasised the need to understand the economics behind future fuels. “What could be the new fuel into the future?” he asked, noting that two-thirds of the problem is solved by SAF alone. Drawing parallels to the renewable energy revolution, he highlighted how solar costs tumbled as scale and supply chains improved. Similarly, he argued, SAF cost curves could fall—“I still don’t see the price dropping from 3x to 1x… but maybe there is a downward movement.” For India, he pointed to municipal solid waste (MSW-to-fuel) as a promising pathway—especially given India’s waste management crisis. Yet the challenge remains: without the right signals—policy clarity, feedstock strategy, investment incentives—the supply chain cannot mature.

Mukund Santhanam, India Lead at Airborne Capital, brought the asset management perspective, explaining how sustainability concerns are already affecting aircraft values globally. As a lessor, he emphasised the need to understand the economics behind future fuels. “What could be the new fuel into the future?” he asked, noting that two-thirds of the problem is solved by SAF alone. Drawing parallels to the renewable energy revolution, he highlighted how solar costs tumbled as scale and supply chains improved. Similarly, he argued, SAF cost curves could fall—“I still don’t see the price dropping from 3x to 1x… but maybe there is a downward movement.” For India, he pointed to municipal solid waste (MSW-to-fuel) as a promising pathway—especially given India’s waste management crisis. Yet the challenge remains: without the right signals—policy clarity, feedstock strategy, investment incentives—the supply chain cannot mature.

The final session of Aviation India 2025 drove home a powerful message: India’s sustainable aviation transition is no longer about technological possibility, but about alignment, affordability, and policy direction. As Vasudevan summarised, “The global debate is no longer on whether SAF will scale… it boils down to who pays for it, who produces it, and who benefits from it.”

Across the panel, optimism was evident. There is feedstock potential, investor interest, international momentum, and domestic readiness. But the missing piece—the catalyst—is a clear and comprehensive national policy framework that brings together producers, airlines, regulators, financiers, and technology partners. The message from the panellists was unanimous: India can be a global SAF leader, but only if industry collaboration is matched with policy ambition. As the session closed, the room shared a sense that the conversation had moved from conceptual to actionable—an essential shift for an aviation market expected to be one of the world’s largest in the decades ahead. Aviation India 2025 did not just end with a panel discussion. It ended with a call to action for India’s greener skies.