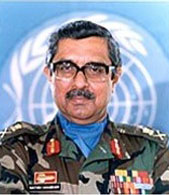

By Lt Gen Satish Nambiar (Retd.)

New Delhi. 03 April 2020. Let me start with my personal experience on the subject by stating that command of the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR) in the former Yugoslavia in 1992/93 was a great honour & a privilege. It was a professional challenge that was in many ways the high point of my Service career. Something I look back to with a great sense of achievement, satisfaction and fulfilment. I had the unique privilege of having uniformed personnel from about 34 countries of the world under my command and many more in the civilian field. Without any reservations whatsoever, or an attempt at false modesty, I attribute my ability to have been able to handle the assignment effectively to the excellent grounding received in the Indian Army and the high standards of professionalism that are the hallmarks of our system. Most of you are probably not aware that I did NOT have any Indian representation on the Mission other than a personal staff officer from the Mechanised Infantry Regiment of which I was then the ‘Colonel’. Philip Campose went in with me as a major and picked up the rank of lieutenant colonel there in a few months. (Incidentally, he retired as the Vice Chief of Army Staff about five years back).

That experience provided me with an unforgettable insight into how the international system operates: the political machinations that are the every-day feature of international activity; the rhetoric and symbolism indulged in by many world leaders and by the governments they represented. In quite a few cases I was privy to the utter hypocrisy of the international community. Which needless to say, made me a total cynic; a malaise that still lingers. Even so, it was a tremendous experience; because in addition to dealing with the top leadership of the parties to the conflict in the normal course, I had occasion to interact with many eminent international personalities at various levels.

The second point I wish to make is that I was struck by the dedication of all contingents to the UN as an organisation and to its principles and ideals; almost without exception despite the fact that many countries were providing personnel for UN peacekeeping for the first time. Also the fact that all personnel including civilians, were more than willing to undergo difficulties and face danger without complaining. For all its inadequacies (without doubt many), there does not, at the moment, seem to be anything else to replace the UN. So we must make it work and work well.

Most analysts who have presumed to address the UNPROFOR experience have generally glossed over the fact that the mission was actually set up in March 1992 to deal with the situation in Croatia after a cease-fire was agreed to by the then federal authorities in Belgrade and the newly declared independent Croatian government in Zagreb; for protection of areas within Croatia that had significant Serb minority populations. Ironically, to carry out that task, we were mandated to set up the Mission Headquarters in Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH) which was at that time (March 1992), still a constituent of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY). As it happened, even before the deployment for the tasks in Croatia was completed, BiH literally blew up under our noses in the first week of May 1992. Talks sponsored by the European Economic Community (EEC as it then was) collapsed, fighting broke out between the Muslims, Serbs and the Croats within BiH, and to cap it all, the Europeans followed by the USA, recognised BiH as an independent republic. As a result, elements of the Yugoslav National Army (JNA) deployed in BiH became a new factor in the equation; the Bosnian Serb component detached from the JNA and remained within the Republic to fight for what they perceived was the Serb cause, while the remainder that had affiliation to Serbia-Montenegro withdrew into the territories of what was left of the FRY.

This prelude was necessary in order to have a clear idea about what the mission had to deal with. By about mid 1992, despite the problems I was faced with handling the situation in Croatia, I was being saddled with additional mandates for BiH, like keeping Sarajevo airport open for induction of humanitarian aid, border control mechanisms, escort of humanitarian aid road convoys, and in due course, monitoring of a no-fly-zone, etc. In so far as the Croatian situation was concerned, whereas there was no resumption of hostilities, there was much posturing and manoeuvring. In which, sad to say, the USA and the major European powers played a rather dubious role by undermining the mandate of the Mission through the political support extended to the Croatian authorities; at another level this was compounded by similar support extended to the Serbs by the Russian contingent.

Within BiH, the deteriorating situation led to a UN Sec Co Resolution providing additional forces for deployment into the Republic for protection of humanitarian aid convoys, for monitoring exchange of fire by the belligerents, etc. The main components were from France, Spain, the UK, Canada, the Scandinavian countries, and a contingent each from Ukraine and Egypt. To exercise command of these forces, between Marrack Goulding (the then USG DPKO) and I, we agreed that my then Deputy Force Commander, French General Philipe Morillon would set up a sector headquarters in Sarajevo that would function under my overall command. Staff for this headquarters was provided primarily by the Europeans, through the aegis as it eventually turned out, of NATO resources. Needless to say, besides the thankless day-to-day problems of dealing with the political leadership of the parties to the conflict, and their warring forces, I found myself having to deal with rather disingenuous efforts by the Americans and the Europeans to smuggle in equipment and personnel for surveillance and intelligence gathering; both of which in those days were taboo in UN peacekeeping. Such activity together with occasional instances of weapons and equipment being smuggled in through UNHCR convoys, made the Mission’s position rather awkward to put it mildly. When the issue was raised, I received an apology from the French, a denial from the UK, and no response from the US authorities.

To the eternal credit of my senior colleagues in the Mission from NATO countries, I must say that not only were they acutely embarrassed by what was being done by their masters in Brussels and respective capitals, but they discreetly kept me informed about what was going on. As a consequence of which, I was invariably in a position to keep things under control. To that extent, I take immense satisfaction in the fact that I was able to command such confidence and respect from a bunch of guys who were outstanding professionals in their own right.

I was on a one-year contract with the UN from 03 March 1992 to 02 March 1993, initially in the grade of Assistant Secretary General, and later as the Mission content and responsibility grew, my status was upgraded to that of Under Secretary General. By mid February 1993 I had made up my mind that I would return to the rolls of the Indian Army on completion of my contract period. On reaching this decision, I tried to contact General SF Rodrigues, my then Chief of Army Staff. He was away on tour and could not be contacted. Hence I spoke to the late JN Dixit the then Foreign Secretary and explained my reasons for the step I proposed to take. He endorsed my decision without any hesitation. It is another matter altogether that on return to India, I was asked, apparently at the instance of the then Defence Secretary, NN Vohra for an explanation as to why I declined the offer of extension without consulting the Ministry of Defence. Possibly out of pique that I found it appropriate to speak to the Foreign Secretary rather than to the Defence Secretary. It is again another matter that within a couple of years of our, more or less simultaneous retirement, both of us developed a tremendous relationship and great respect for one another; and worked together on a number of “task forces”, “committees” and so on. The action I took was possibly the first (and maybe the only) instance in the history of the UN where a person at the level of USG declined an extension in an appointment.

Kofi Annan who had taken over as USG DPKO from Marrack Goulding was obviously bowled over by my request for reversion to national duties on completion of the terms of the contract. While he was recovering from the impact of my request, I was frantically contacted by James Aimee, then the late Boutros Boutros Ghali’s Chef-de-Cabinet, among others, not to insist on leaving. Seeking their indulgence and understanding, I asked them to look for another person to replace me. Since I did not wish to embarrass the SG or the UN, nor did I wish to make the already difficult task of my colleagues in the Mission any more awkward than it already was, the media was informed that I was declining the offer of extension due to family commitments.

For the record, the actual reasons were two. As it happened, in mid-February 1993, my senior civil affairs staff showed me a copy of a noting initiated in DPKO at the instance of some powerful members of the Security Council at that time asking for a restructuring of the command arrangements of UNPROFOR, to bring in an SRSG (Special Representative of the Secretary General) to oversee the operations of the Mission, with the Force Commander to be responsible only for exercising control over the military component; as in most major complex UN missions. Those of you who take the trouble to read the UN Sec Co Resolution of 15 February 1992 setting up UNROFOR, will find that the unique arrangement that I was mandated to undertake was a specific exception consciously taken at that time; that as the Force Commander I would also exercise full oversight over the political, civil affairs, civilian police and administrative content of the mission besides of course, the military. That I was made aware of developments taking place in New York in February 1993 is a reflection of the fact that the UN system leaks like a sieve. While I had no problems with what was proposed, I saw no reason, as someone who had been Number “One”, accepting a status of being Number “Two”. It had nothing to do with ego; I just did not relish the idea.

But the second and equally important reason was what I perceived as efforts by NATO to intrude into the running of what was a UN mission (discreet as they were). There was no way I as the Head of the Mission would have allowed that to happen. And I was also clear that in any confrontation between “NATO” and “Satish Nambiar”, there could be only one loser.

I was therefore not surprised to hear, about three months after I had left, that what I anticipated did in fact take place. My successor, the late General Lars Eric Wahlgren from Sweden (who I incidentally inter-acted with a number of times in later years) was somewhat unceremoniously replaced as the Force Commander in mid 1993 by a French General (Cot) with a change of command structure that brought in the former Norwegian Foreign Minister Stoltenberg (not to be confused with his son who became Prime Minister of Norway) as SRSG. I am sure Yasushi Akashi of Japan who took over the assignment later would confirm the discomfort he was subjected to by the intrusion of NATO into the conduct of mission operations. I also had occasion to talk with British General Michael Rose who commanded the forces in BiH after Morillon and became privy to his frustration.

Today vivid memories of my experience as the first Force Commander and Head of Mission of the United Nations Protection Force in the former Yugoslavia (UNPROFOR) from 3rd March 1992 to 2nd March 1993 have revived and reminded me of the fact that had the international community then addressed the situation in the proper perspective, the incident should never have taken place. Nor the genocide in Rwanda where many more innocent civilians became victims. The unfortunate irony is that all too often, rhetoric and symbolism replace logic and action, in the hallowed portals of the Security Council chambers. And in that knowledge I feel prompted to relate one of the experiences as the Head of that Mission that has a bearing on the subject even if somewhat indirectly.

Starting with a reminder to the analysts and historians who set out views on the Balkans crisis of the early 1990s, that UNPROFOR was set up to deal with the situation in Croatia, and without going into the other details of the Mission, let me state that by early May 1992 the Mission was faced with the reality of Bosnia-Herzegovina (BiH) blowing up under our noses, as it were, situated as the Mission Headquarters then was; in Sarajevo.

Remaining on the main theme of this piece, by October 1992 (by which time the Mission Headquarters had been relocated to Zagreb), there was much fighting taking place between the three communities in BiH (Muslim, Serb and Croat). In recognition of which, the UN Security Council had mandated UNPROFOR with a number of responsibilities, including keeping Sarajevo airport open for the induction of humanitarian aid supplies, etc. There was yet no peacekeeping mandate for Bosnia-Herzegovina; at least not till I left the mission on 2nd March 1993. To provide the ‘muscle’ for execution of the mandate of humanitarian assistance, additional contingents from France, United Kingdom, Spain, Canada, Egypt, and Ukraine, were made available, and a Sector headquarters set up in Sarajevo. With my concurrence, Phillipe Morillon , my French Deputy Force Commander and great friend and colleague, was deputed to head the forces in BiH, and replaced on my staff by an equally competent Canadian General, Robert Gaudreau.

Sometime in the third week of October 1992, I received a frantic call from Marrack Goulding, the then Under Secretary General for UN Peacekeeping, apprising me that there was great pressure on the UN SG (Boutros Boutros Ghali) and UN DPKO to initiate measures to declare seven areas, including Sarajevo, that were then under threat in BiH, as “safe areas”. In response, I enquired from him what, was the perception of a “safe area” in New York. After a minute’s silence he candidly admitted they did not have the ‘foggiest’ idea, and asked me what my interpretation was. Without any hesitation whatsoever, I gave him my military interpretation; in brief, that a “safe area” is a geographically delineated entity, which would be secured militarily all around, then cleared on the inside of all unauthorised weapons and ammunition, and entry into the area would be physically monitored by armed UN troops to ensure that no armed personnel from outside be permitted entry, nor would any weapons or lethal equipment be allowed in. That interpretation appeared to be logical enough to satisfy Marrack. He then asked me what resources I would require to implement the task of securing the designated “safe areas”. Needless to say, my response was that I would require at least 24 hours for working out the details in consultation with my sub-ordinate commanders and staff.

My staff in Zagreb that included the Deputy Head of Mission and Director Civil Affairs Cedric Thornberry, Deputy Force Commander, Major General Gaudreau , Chief of Staff, Danish Brigadier General, Svend Harders, together with Lieutenant General Phillipe Morillon and his staff in Sarajevo led by, a British Major General Cordy Smith, and many others, worked over 24 hours to produce an eminently workable arrangement, that I endorsed with some marginal adjustments. The next evening (given the time difference between Zagreb and New York) when Marrack Goulding called me, I was in a position to give him a well thought out military assessment for implementing a “safe area” concept in BiH. Responding to his query about the requirement of troops to execute the tasks, I informed him that, as worked out by the Mission, we would require an additional force of four and a half divisions (approximately 55,000 to 60,000 troops) to implement such a mandate. I imagine that he would have almost fallen off his chair in New York on hearing that.

As it happened, Marrack Goulding thanked me for the response and signed off. I did not hear anything more on the subject till I left the mission on 2nd March 1993 on completion of my contractual obligation of one year, and declining an offer of extension. It was therefore with deep regret and some consternation that, in following events in the Balkans after my return to India, I noted the declaration of places like Srebrenica as “safe areas” without deployment of the requisite number of troops. To that extent, the genocide at Srebrenica was without doubt a failure of the international community represented by the United Nations. (As was Rwanda)

It would not possibly surprise discerning practitioners and maybe some analysts, that when IFOR forces moved into Bosnia-Herzegovina after the signing of the Dayton Agreement, the total troop strength was about 60,000. More or less the same strength worked out by us in UNPROFOR in October 1992; and that without agreement to a cease-fire by the parties to the conflict.

It is possibly appropriate to conclude this piece by recalling what India’s then Permanent Representative to the UN, Ambassador Hardeep Puri had to say on 24 July 2009 during the debate in the General Assembly pertaining to the concept of the ‘Responsibility to Protect’: “It has been India’s consistent view that the responsibility to protect its population is one of the foremost responsibilities of every state”. He stressed that “Willingness to take Chapter VII measures can only be on a case-by-case basis and in cooperation with relevant regional organisations with a specific proviso that such action should only be taken when peaceful means are inadequate and national authorities manifestly fail in discharging their duty”. In emphasising the need to be realistic he further stated, “We do not live in an ideal world and therefore need to be cognisant that creation of new norms should at the same time completely safeguard against their misuse. In this context, responsibility to protect should in no way provide a pretext for humanitarian intervention or unilateral action.” And he concluded thus: “Even a cursory examination of reasons for non-action by the UN, specially the Security Council, reveals that in respect of the tragic events that were witnessed by the entire world, non-action was not due to lack of warning, resources or the barrier of state sovereignty, but because of strategic, political or economic considerations of those on whom the present international architecture had placed the onus to act. The key aspect therefore is to address the issue of willingness to act, in which context a necessary ingredient is real reform of the decision making bodies in the UN like the Security Council in its permanent membership.”

(Lt Gen Satish Nambiar(Retd) of the Indian Army was the first Force Commander and Head of Mission of UNPROFOR, the United Nations Protection Force. The views in the article are solely the author’s. He can be contacted at editor.adu@gmail.com)