- India Must Dominate the Lower Airspace

- Lower Skies, Higher Stakes : Calls for Indigenous Drone and Counter-UAS Ecosystem

- Drones Are at the Heart of India’s Next Military Revolution

By Sangeeta Saxena

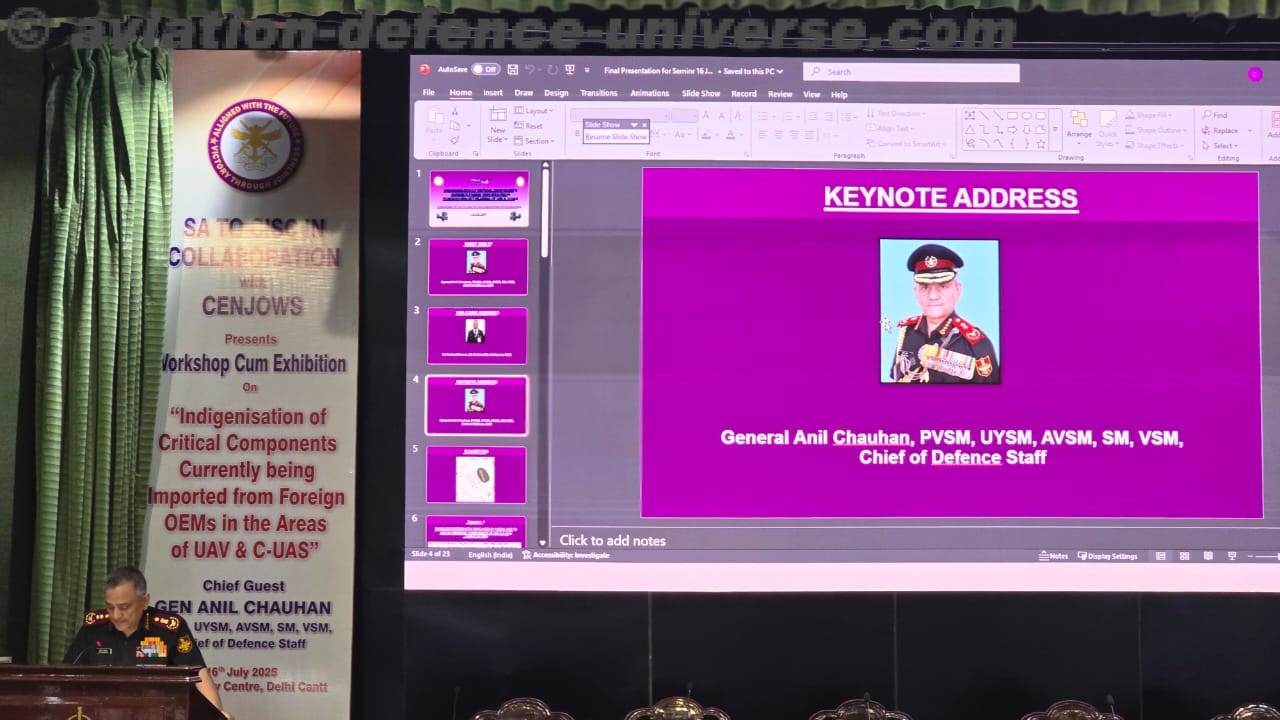

New Delhi. 16 July 2025. “We are at the cusp of a third revolution in military affairs—one that is data-centric and driven by advances in artificial intelligence. Drones lie at the heart of this shift. Their development may have been evolutionary, but their employment in warfare has been nothing short of revolutionary. Drones evolved from tools of simple videography to cost-effective force multipliers. They have proven their utility in modern conflicts by enabling simultaneous operations across domains with  minimal danger to human life. Their very nature defies conventional warfare logic—and that is what makes them powerful. In Operation Sindoor, Pakistan employed unarmed drones and low-altitude missiles. Our layered kinetic and non-kinetic response ensured they caused no damage to military or civil assets. Many drones were recovered almost intact—proving our growing counter-UAS capability,” stated Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) General Anil Chauhan’s while inaugurating the seminar on “Indigenisation of Critical Components Currently Being Imported from Foreign OEMs in the Areas of UAV and C-UAS”, organised by the Scientific Advisor to the Chief of Integrated Defence Staff to the Chairman Chiefs of Staff Committee (CISC) in collaboration with CENJOWS.

minimal danger to human life. Their very nature defies conventional warfare logic—and that is what makes them powerful. In Operation Sindoor, Pakistan employed unarmed drones and low-altitude missiles. Our layered kinetic and non-kinetic response ensured they caused no damage to military or civil assets. Many drones were recovered almost intact—proving our growing counter-UAS capability,” stated Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) General Anil Chauhan’s while inaugurating the seminar on “Indigenisation of Critical Components Currently Being Imported from Foreign OEMs in the Areas of UAV and C-UAS”, organised by the Scientific Advisor to the Chief of Integrated Defence Staff to the Chairman Chiefs of Staff Committee (CISC) in collaboration with CENJOWS.

Operation Sindoor marked a defining moment in India’s contemporary security landscape, particularly highlighting the evolving threat of hostile drones and loitering munitions. Pakistan’s coordinated use of UAVs and low-flying projectiles exposed the vulnerability of Indian defence systems to foreign-built drone swarms and payload delivery mechanisms. While Indian forces successfully neutralised incoming threats through layered kinetic and electronic responses, the incident reaffirmed the need for autonomous, secure, and rapidly scalable UAV systems—ones that are not beholden to foreign supply chains. Imported drones and components, whose capabilities are well-known to adversaries, erode the element of strategic surprise. In contrast, indigenously developed systems allow for customised performance, classified technologies, and operational secrecy—critical advantages in the new age of grey zone warfare and low-intensity conflict.

“We must develop indigenous counter-UAS systems tailored to our terrain and threats. Imported niche technologies expose our vulnerabilities. Their capabilities are known to the adversary, allowing them to predict tactics and sidestep our advantages. Homegrown systems preserve surprise and scalability. Airspace is no longer indivisible. The lower airspace—below traditional altitudes—is now the most contested and congested. We need to dominate this layer using drones and counter-UAS technologies while denying its use to the adversary. Effective counter-UAS operations require a robust grid integrating radars, jammers, sensors, and directed-energy weapons. It’s not just about technology—it’s about adaptive architecture and seamless coordination between air defence, civil aviation, regulators, and ground forces,” CDS added.

Unmanned systems have emerged as pivotal force multipliers in modern warfare, transforming the tactical and strategic landscape across conflict zones. The Russia-Ukraine war has underscored the game-changing role of drones—from low-cost commercial quadcopters used for battlefield surveillance and artillery targeting to long-range loitering munitions like the Iranian-made Shahed drones employed by Russia. Similarly, Hamas leveraged small drones and loitering UAVs for both surveillance and offensive missions during its conflict with Israel, showcasing how non-state actors can use asymmetric drone warfare to bypass conventional defences. In the short but intense Israel-Iran confrontation, waves of drones were deployed alongside missiles in a coordinated assault, reinforcing the reality that unmanned aerial threats can now rival conventional airpower in both scale and impact.

Unmanned systems have emerged as pivotal force multipliers in modern warfare, transforming the tactical and strategic landscape across conflict zones. The Russia-Ukraine war has underscored the game-changing role of drones—from low-cost commercial quadcopters used for battlefield surveillance and artillery targeting to long-range loitering munitions like the Iranian-made Shahed drones employed by Russia. Similarly, Hamas leveraged small drones and loitering UAVs for both surveillance and offensive missions during its conflict with Israel, showcasing how non-state actors can use asymmetric drone warfare to bypass conventional defences. In the short but intense Israel-Iran confrontation, waves of drones were deployed alongside missiles in a coordinated assault, reinforcing the reality that unmanned aerial threats can now rival conventional airpower in both scale and impact.

“We must boost defence R&D, adopt modular and upgradable designs, standardise open architectures, and invest in stealth, AI-powered counter-UAS systems, and secure software stacks. Our startups and academic institutions must be given testbeds to innovate. Today’s warfare demands tomorrow’s technologies. We can’t rely on yesterday’s systems to win future battles. Atmanirbharta is not a choice—it is our duty. This seminar and the accompanying exhibition are vital steps in evolving India’s UAV and C-UAS roadmap. I encourage all stakeholders to contribute to making India self-reliant and future-ready in this critical domain, ” Gen Anil Chauhan reiterated.

India’s growing reliance on unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) for surveillance, intelligence gathering, and strike capabilities has exposed a critical strategic vulnerability—its dependence on imported components. Essential parts such as sensors, gyroscopes, inertial navigation systems, flight control units, lithium polymer batteries, communication systems, and EO/IR payloads are predominantly sourced from China, Europe, and the United States. This foreign dependence creates operational risks, especially in times of geopolitical tension, sanctions, or supply chain disruptions. Chinese components, though widely available and cost-effective, raise serious concerns over cybersecurity, data integrity, and reliability. Western components, on the other hand, are often restricted under export controls and may be denied during critical periods. In essence, India’s UAV ambitions are tightly linked to the geopolitical climate of its suppliers.

“I’m happy to note that this workshop is deliberating on crucial issues for implementation and improvement in existing U.S. and counter-U.S. capabilities. I would like all of you during the day’s deliberation to focus on a few things. First, I think, is increased impetus on defence R&D to deliver next generation of solutions. Then, encourage modular, upgradable design so that new technology payloads, AI modules, EW technology can be integrated quickly. Next develop standardised open architecture for plug-in remodels for effective counter-U.S. both for kinetic and non-kinetic systems. After this create counter-UAS system testbeds. Then invest in secure software stacks for UAV control and anti-damage. Finally we will focus on stealth and next generation of UAVs. And last and not the least, develop a long-term vision roadmap for strong drones, drone carriers, MUMT, direct energy weapons, artificial intelligence-powered counter-U.S. systems.

“I’m happy to note that this workshop is deliberating on crucial issues for implementation and improvement in existing U.S. and counter-U.S. capabilities. I would like all of you during the day’s deliberation to focus on a few things. First, I think, is increased impetus on defence R&D to deliver next generation of solutions. Then, encourage modular, upgradable design so that new technology payloads, AI modules, EW technology can be integrated quickly. Next develop standardised open architecture for plug-in remodels for effective counter-U.S. both for kinetic and non-kinetic systems. After this create counter-UAS system testbeds. Then invest in secure software stacks for UAV control and anti-damage. Finally we will focus on stealth and next generation of UAVs. And last and not the least, develop a long-term vision roadmap for strong drones, drone carriers, MUMT, direct energy weapons, artificial intelligence-powered counter-U.S. systems.

Chauhan stressed, “We cannot rely on imported niche technology that are crucial for our offensive and defensive missions. We must invent and build and safeguard ourselves. Dependence on foreign technologies weakens our preparedness, limits our ability to scale our production, results in shortfall of critical spares for sustenance, and round-the-clock availability. Another important aspect of this capability is that foreign weapons and sensors, their capabilities are known to all, and adversaries can predict our tactics and optional concepts based on the capabilities of this particular system. So you may have today on very modern aircraft, air-to-air missiles whose ranges are known to us, so are they known to the adversaries also.

At the moment, if they are imported, then obviously the adversary can keep out of those ranges and develop tactics for them. So this becomes a severe limitation, but if you are developing systems which you own, their capabilities are not known to the enemy, and that will add an element of surprise when actually you are face-to-face in some initial encounters, at least. So when we design, make, and innovate at home, we secure our secrets, cut costs, retain the initiative to scale our production, and maintain round-the-clock readiness.”

At the moment, if they are imported, then obviously the adversary can keep out of those ranges and develop tactics for them. So this becomes a severe limitation, but if you are developing systems which you own, their capabilities are not known to the enemy, and that will add an element of surprise when actually you are face-to-face in some initial encounters, at least. So when we design, make, and innovate at home, we secure our secrets, cut costs, retain the initiative to scale our production, and maintain round-the-clock readiness.”

CDS restated that the lower airspace has become the primary domain of combat in contemporary warfare, particularly due to the proliferation of drones and unmanned systems. The strategic imperative for the armed forces is twofold – to harness this airspace effectively through the deployment of force multipliers such as unmanned systems and simultaneously to deter adversaries from exploiting it by developing a robust counter-unmanned systems framework. As warfare increasingly shifts to this contested lower airspace, it is vital to focus future combat readiness on this dimension. The potential to enhance drone range and functionality significantly increases with the integration of advanced technologies like LEO satellites, which offer improved control, communication, and navigation services. Conventional drones, limited by line-of-sight data link constraints, cannot match the extended reach enabled by satellite-based control. In this evolving battlespace, the development of counter-UAS systems becomes critical. These systems must be capable of safeguarding key military and civilian installations as drones and autonomous platforms become the weapons of choice for precision strikes and surveillance.

He also reckoned counter-drone operations are inherently complex, involving the detection, identification, tracking, and neutralisation of hostile drones. This requires the establishment of a sophisticated counter-U.S. grid, integrating diverse technologies such as radars, electro-optical sensors, jammers, and directed energy weapons. The grid’s effectiveness will depend on seamless coordination between air defence systems, civil aviation authorities, regulators, and local command and control units to prevent gaps and operational blind spots. Ultimately, modern counter- drone architecture is not solely about advanced hardware; it is about fusing disparate assets into a resilient, adaptive ecosystem and incorporate indigenously developed drone and counter-drone systems, tailored specifically for India’s operational environments and strategic requirements.

He also reckoned counter-drone operations are inherently complex, involving the detection, identification, tracking, and neutralisation of hostile drones. This requires the establishment of a sophisticated counter-U.S. grid, integrating diverse technologies such as radars, electro-optical sensors, jammers, and directed energy weapons. The grid’s effectiveness will depend on seamless coordination between air defence systems, civil aviation authorities, regulators, and local command and control units to prevent gaps and operational blind spots. Ultimately, modern counter- drone architecture is not solely about advanced hardware; it is about fusing disparate assets into a resilient, adaptive ecosystem and incorporate indigenously developed drone and counter-drone systems, tailored specifically for India’s operational environments and strategic requirements.

India must urgently accelerate its push for self-reliance in critical UAV components through Atmanirbhar Bharat initiatives, enhanced DRDO programs, and robust public-private R&D collaboration. Indigenous manufacturing ensures supply chain security, cost efficiency, and faster upgrades tailored to Indian operational environments—from deserts to high-altitude battlefields. Beyond traditional defence PSUs, startups, academia, and MSMEs must be integrated into the defence innovation ecosystem through testbeds, procurement incentives, and standardised open architecture platforms.

India must urgently accelerate its push for self-reliance in critical UAV components through Atmanirbhar Bharat initiatives, enhanced DRDO programs, and robust public-private R&D collaboration. Indigenous manufacturing ensures supply chain security, cost efficiency, and faster upgrades tailored to Indian operational environments—from deserts to high-altitude battlefields. Beyond traditional defence PSUs, startups, academia, and MSMEs must be integrated into the defence innovation ecosystem through testbeds, procurement incentives, and standardised open architecture platforms.

Indigenous capabilities also ensure that future counter-UAS and drone swarming technologies—powered by AI, secure software stacks, and electronic warfare—can evolve without fear of espionage or backdoor exploits. In the face of increasing volatility and the emerging UAV arms race, building a sovereign drone ecosystem is not just strategic—it is essential for India’s national security. The unmanned industry fraternity showcased their capabilities, Indian armed forces and para military forces put forth their requirement and DRDO and MoD talked about existing facilities which should and can be utilised and what the industry can do to make the ecosystem complete.