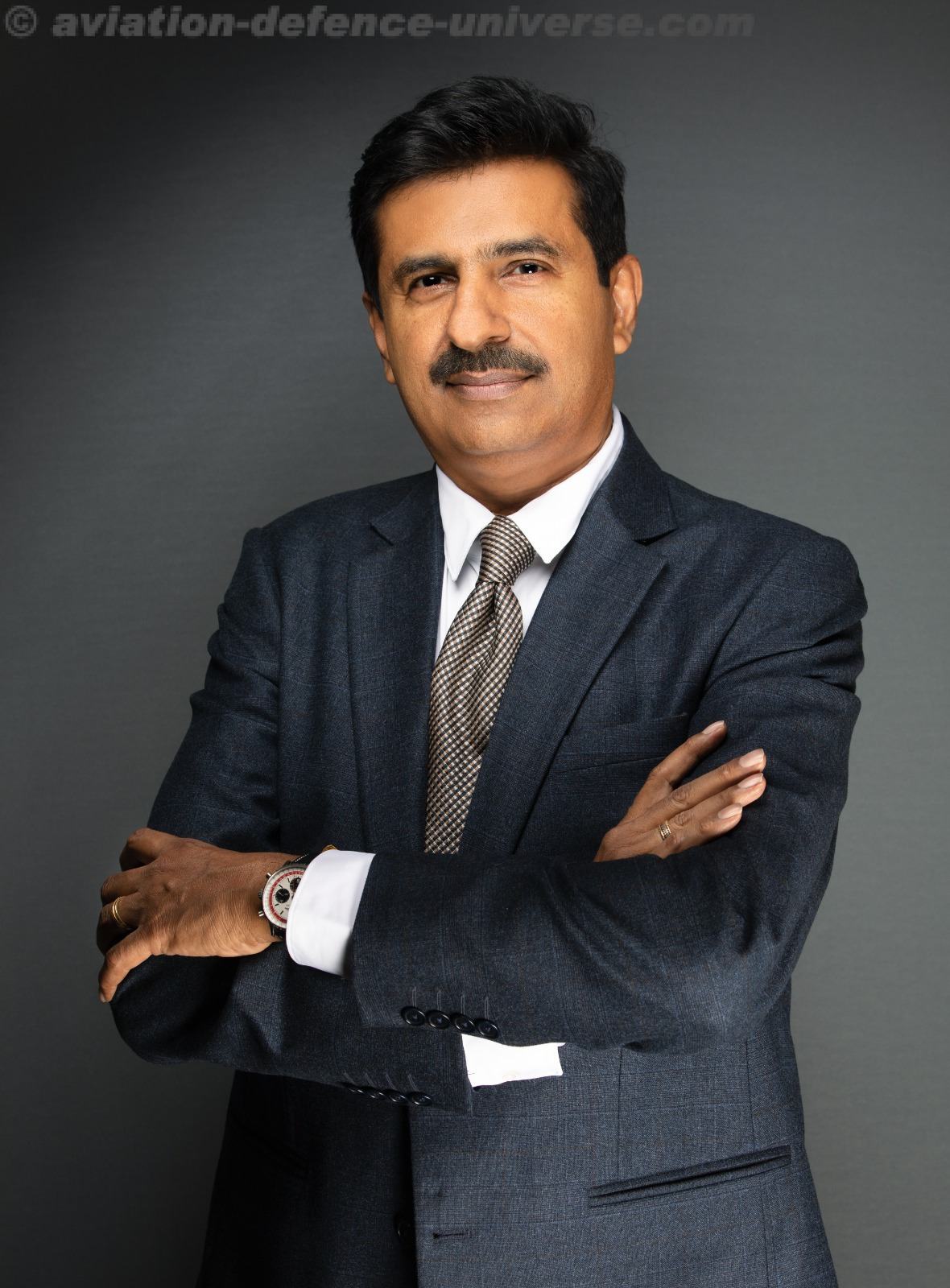

By Maj Gen Ashok Kumar, VSM (Retired)

Lucknow. 11 December 2021. Language is defined as the principal method of human communication, consisting of words used in a structured and formatted way and conveyed either by speech, writing or gesture. Though there are multiple emotions connected with language, its prime importance lies in helping us express our feelings, desires and aspirations. It also acts as a base and a cause for uniting communities within specific geographic areas. While language has ignited a number of revolutions for peoples yearning for nation-states, including use of codified Hebrew in Israel, but the role of Bangla language in being the utmost arbiter of Bengali liberation in East Pakistan during 1971 has not been surpassed so far.

Disconnected Nations Disconnected States.

When India was forced into a Partition no one really wanted or had envisaged, the nation-state of Pakistan was born. Formed by clumping together a number of disparate communities with no lived experience of living or co-existing together before 1947 as part of a single political entity, the only supposedly unifying factor was religion. The two ‘Pakistans’ East & West were themselves separated by 1000 km of Indian landmass. Commonalities between the two separated geographies in terms of culture, customs, language, food, habits just did not exist. The two common factors – both being Muslim majority and part of an overarching state called Pakistan – were not as binding or sacred as the emergence of Bangladesh later showed. Even the Muslims in East Pakistan considered themselves Bengalis first and Bengali language as part of a shared heritage with their West Bengali counterparts. Language formed the bedrock of Bengali national consciousness rather than religion. These incongruent conditions between the two halves of Pakistan kept widening from 1947 till 1970 when beginning 1971, the situation was ripe for the rise of a new Bangla nation – Bangladesh.

Bengali Language as Unifying Force

Though mentioned in passing or given short shrift by a majority of analysts, the Bengali language proved to be the foundation over which the entire liberation movement was fought and won. Immediately after Partition, discrimination commenced against the residents of East Pakistan as the entire power centre was concentrated in West Pakistan and that too, Pakistani Punjab. There were also cultural tropes of Bengalis being effeminate as compared to the ‘masculine’ Pathans and Punjabis. This stereotyping played a huge role in the non-representation of Bengalis in major law and order portfolios such as bureaucracy and administration as well as the armed forces. Similarly, this partial dehumanisation of the Bengalis ensured that the Pakistani armed forces were brutal in their genocide during Op Torchlight.

In reality, East Pakistan, as opposed to West Pakistan had approximate 28% Hindus and 1% Christians, making the society much more pluralistic and secular in its make up and therefore outlook. Not only this, the land holdings in East Pakistan were much smaller in size and there were the beginnings of a prosperous and ascendant middle class. These conditions too accelerated the growth of the Bangla language, steeped as it was in literature and culture, to act as a unifying force for the Bangla nation which understood that it was being exploited by an alien country. Jinnah’s imposition of Urdu as a mandatory language for all of Pakistan despite Urdu being the language of Mohajirs from India, also formed a major casus belli for the armed movement.

In the opening session of the Pakistan Constituent Assembly in Feb 1948, members from East Pakistan proposed the institution of Bengali language alongside Urdu as the national language, but this proposal was rejected by the then Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, on the grounds that this will create grounds for internal division within the country. This issue however caught the attention of a majority of people in East Pakistan. A National Language Struggle Committee was formed to ensure that Bangla language also received recognition as a national language. The thought and the proposal was pragmatic as it allowed for the co-existence of both languages.

While the language movement was taking a defined shape, Mohammad Ali Jinnah paid a maiden visit to Dacca on 21 Mar 1948 and spoke vehemently against the two-language concept as he strongly believed that Urdu as the sole official and national language was required to keep Pakistan whole and united. This speech was a subset of a movement that believed that a common language bound people more intimately but this was just one part of the complex issue of nation-hood and how it related to the creation and sustenance of a state. Culture, history, population profile and finally a contingency of factors, decided how well people bonded with each other. In the case of East Pakistan, such dissimilarities from West Pakistan existed but these were disregarded and Urdu was imposed as a national language. This decision dented the self-respect of the Bengalis and Bengali language thus became a rallying cry for autonomy (subsequently converted to nationhood) across the entire length and breadth of East Pakistan. This continued language movement in intensified form forced the Pakistani government to accept Bengali as national language in 1956 when the first iteration of Pakistan’s constantly changing Constitution was adopted.

This short lived achievement, however, was doomed when President Iskander Mirza imposed martial law on 30 Sep 1958 suspending the Constitution, terminating the aspirations of a large number of East Pakistani residents to history’s dustbin, to say the least. The above notwithstanding, residents of then East Pakistan had realised the power of Bengali language as a unifying force and also the capacity of the said movement to generate positive outcomes. 21 Feb is also regarded as International Mother Language Day and this very date is a national day for Bangladesh to commemorate the protests and sacrifices that preserved Bengali language for the Bangla nation. While the language movement continued in some form or the other, it formed the primary substrate for the later autonomy and then independence movement to catalyse itself.

Participation of the East Pakistani masses was essential to achieve the intended aim of nationhood. This was well understood by Bangabandhu Mujib. Post the launch of the Six Point program, whenever differences arose between certain individuals and organisations, the Bengali language became the glue that held the movement together and re-energised all stakeholders.

Conclusion

While a lot has been and can be written on the liberation of Bangladesh, Bengali language played a pivotal role in attaining current day shape of Bangladesh. It is possibly the only country in the world where language movement was the primary one and the cause for a nation attaining independence.

(Maj Gen Ashok Kumar, VSM (Retd) is a Kargil war veteran and defence analyst. He is visiting fellow of CLAWS and specialises on neighbouring countries with special focus on China. The views in the article are solely the author’s. He can be contacted at editor.adu@gmail.com)