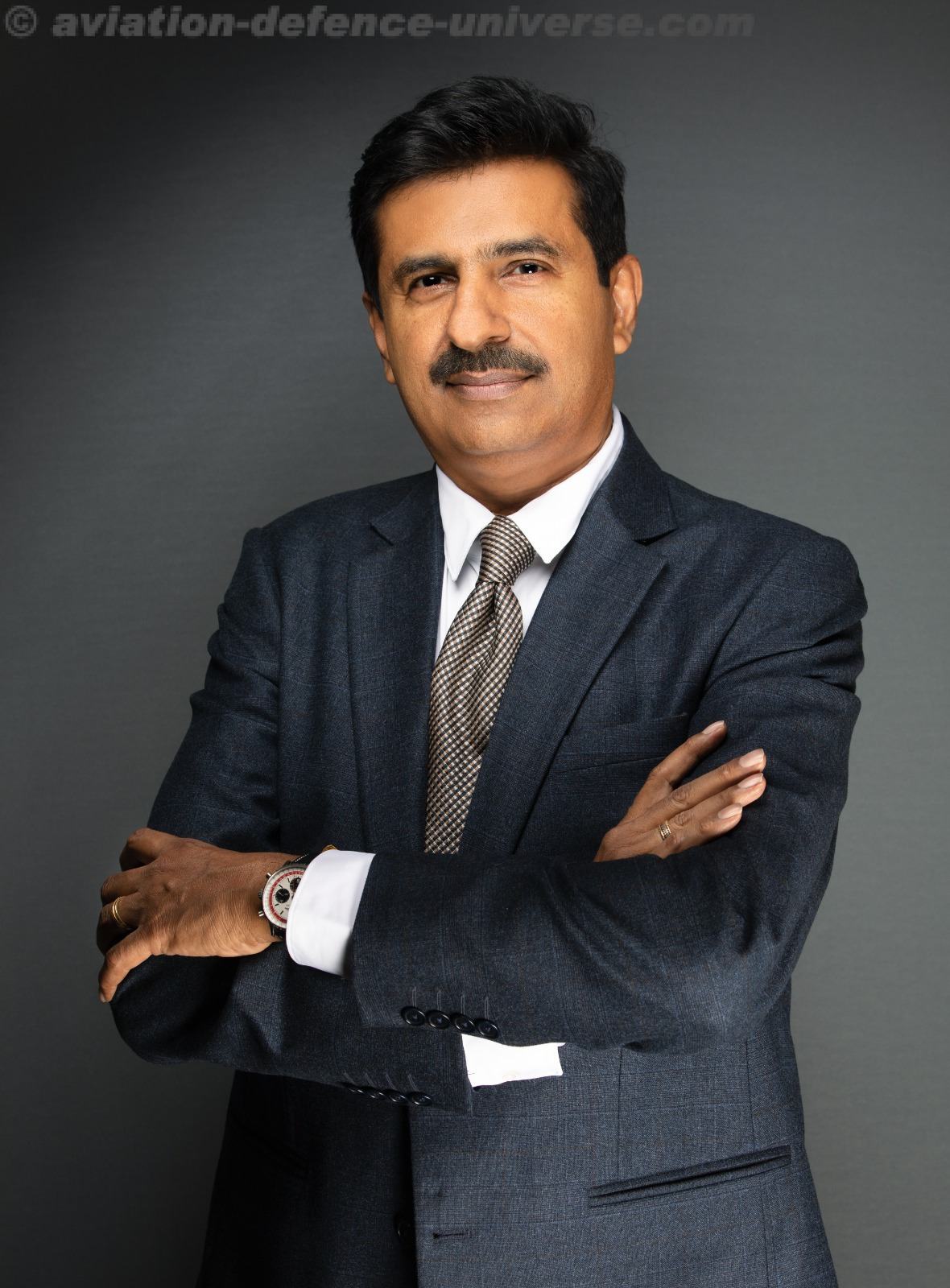

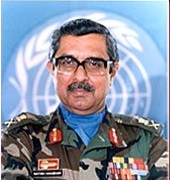

By Padma Bhushan Lieutenant General Satish Nambiar PVSM ,AVSM ,Vr C. (Retd.)

New Delhi. 26 October 2020. In most countries of the Western world, as also in countries like Russia, China, Cuba, East European countries, Vietnam, South Korea, Philippines, Indonesia, and some countries in Africa, significant sections of the political leadership in the second half of the 20th Century, were drawn from those who took active part in the two world wars, the ‘Long March’ in China, the intense battles in Vietnam, and many other smaller scale conflicts. Those countries were therefore run by leaders who had first hand awareness of the demands placed on armed forces personnel, and the sacrifices they make in the service of their countries. Such leaders therefore ensured that armed forces personnel, both those in service, as well as those who had retired, were not only well taken care of, but accorded the dignity and respect they were entitled to, and given their rightful place in the society whose security they have dedicated their lives to. Though the current generation of political leadership in many of these countries no longer have the same numbers as before who would have served in the armed forces, the culture ingrained in those societies of giving respect to and looking after their armed forces personnel, is still carried forward without dilution.

In our case, on attaining Independence from the British in 1947, the Indian political leadership (particularly in the absence of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose and his comrades), notwithstanding outstanding political credentials, had no such experience whatsoever. As it transpired, despite evidence that the departure of the British had much to do with their awareness that they could not continue to rely on the loyalty of the personnel of the Indian Armed Forces (the events of 1857 were a warning, as was the Naval uprising), the political leadership of the time considered it expeditious to propagate the theory that we had secured Independence from the British through purely non-violent means, and that India as a peace loving nation did not require the Armed Forces the country then had. An organization that had done an outstanding job on the battlefields of Europe, Africa, Burma and even in our North Eastern states during World War 2, albeit under the British flag, That theory was all too quickly demolished by the need to respond to the invasion in October 1947 of Jammu and Kashmir by raiders, followed by the Pakistani Army. Shortly thereafter, the Indian Army was tasked to secure Hyderabad in what the then leadership termed as a “Police Action”. In 1961 the Indian Armed forces launched operations to secure Goa, Daman and Diu. However, the country paid a heavy price for the continued neglect of the Armed Forces when the Chinese launched operations against us in October 1962. Notwithstanding the gallant actions of our junior leadership and the rank and file, we paid a heavy price due to the questionable political and senior military leadership of the time. A price we continue to pay even today, both on the Northern borders with Tibet, as also in Jammu and Kashmir, and in Ladakh.

For people of my generation the sad irony in the twilight of our existence, is that despite our unreserved commitment and unswerving loyalty to the Nation, demonstrated time and again, significant sections of the political class that have little or no knowledge about what the profession of arms is about, remain suspicious of the Indian military. This is absolutely unforgivable. It is therefore not surprising that, notwithstanding the occasional rhetoric about the sacrifices the military makes in the service of the Nation, the political leadership is lukewarm at best when it comes to addressing the aspect of dignity and respect of defence personnel. Even more unfortunately, the civilian bureaucracy and the police, with who the political leadership share such an intimate working relationship, are (no doubt with some notable exceptions), downright dismissive, and often antagonistic to the aspect of the status and dignity of defence personnel. An attitude probably further aggravated by the fact that in every national survey conducted about which category of individuals serve the country best, the people at large place personnel from the Indian Armed Forces right on top, on a pedestal well above the politician, bureaucrat and policeman.

In this context, a vital point that needs to be placed in perspective is that, just like the need for “welfare of the poor and the needy”, “farmers with small holdings”, “the handicapped”, etc, we need to address without any reservations whatsoever, aspects of the dignity and respect of defence personnel, as also their welfare and that of their families. Because the military is the only profession that calls upon the individual to make the ultimate sacrifice in performance of one’s duty; that of ‘laying one’s life on the line’ without question. Fortunately, the country goes to war only every now and then. Even so, the fact of the matter is that the Indian defence personnel are deployed ‘round the clock’ on our borders, the Line of Control, the Line of Actual of Control, on counter-insurgency tasks, on counter-terrorism tasks, disaster relief, and so on. And take casualties in the process almost on a daily basis. Allowing their civilian counterparts to sleep in safety and comfort in their homes. Hence it does the establishment no credit to be patronising or condescending on the subject of ensuring the dignity, respect and well-being of defence personnel at all times.

If the Government is serious about giving defence personnel their legitimate due, there is much that needs to be pursued with vigour on aspects that require little or no financial investment. The military-man is not looking for doles from the political dispensation or the country. He (or she) is only looking for the government to do its duty. Which in context of the peculiar conditions of service and circumstances primarily relate to the following:-

- Security and welfare of their families in the villages, to include parents, spouses and children; which translates into understanding, consideration and assistance by the local civil administration and the police.

- The soldier, sailor or airman should not have to go down on his knees to secure admission of his children into good schools, even where he is prepared to pay the high fees that are demanded. Needless to say, the Service schools have done yeoman service in this context. But if an individual wishes to send his ward to a renowned institution, let that be facilitated; it is an investment for the future of the country.

- Security and welfare of widows and children of those who die while in service; in battle or otherwise. In terms of rehabilitation that enables a reasonable quality of life, education of the children and health care.

- The One Rank One Pension issue.

Whereas the preceding paragraphs deal with aspects that fall within the purview of the moral obligation of the Government towards its defence personnel, there is great deal more that can and must be done in terms of the management of manpower in the Armed Forces. Measures that would enable the Government, among other things, to reduce the defence pension bill while harnessing disciplined and trained manpower of the defence forces to more productive purpose in the service of the nation. Though expenditure on defence pensions (which apparently works out to almost three quarters of the pay and allowances outlay in the case of the Army), is not included within the Defence Budget, it has to met from the overall financial resources available to the Government of India. Hence the imperative need to prune expenditure to the extent feasible, by addressing the important aspect of Defence Manpower.

There can be no gainsaying the fact that the quality of manpower inducted into the Indian Armed Forces must always be maintained at the highest levels possible. To that extent, entry level educational, physical and psychological standards cannot be compromised. Equally, pay and allowances offered should, while not necessarily attempting to match levels in the corporate sector, be attractive enough to draw individuals who meet the competence levels that are required today. Equally, terms and conditions of service including avenues for employment on leaving service should be attractive.

As things stand, it appears that for entry at levels below officer rank, there is no serious problem, including for higher grade technical entry in the three Services. However, given the operational imperative for a youthful profile, recommendations have been made in the past for implementing an arrangement for a specified period of colour service together with an appropriate reserve liability period. Such an arrangement presupposes that those who complete the period of colour service are afforded the following options; subject of course, to reserve liability:-

- Pursue a choice of their own; in which case the government has no further role to play, other than continuing to provide such personnel with some facilities that accrue to them by virtue of their service in the defence forces..

- Lateral induction for service till the permissible retirement age (of 60 or as determined from time to time) in the para-military forces, Central or State police, public sector undertakings, etc. The private sector could also be encouraged to exploit this treasure of human resource.

- Those who wish to continue in the defence forces and are considered fit for promotion to the ranks of non commissioned and junior-commissioned officers should be absorbed for retention for appropriate periods after which they should be entitled to pensionary benefits, free medical treatment for themselves and families, and other facilities.

The above options are without prejudice to the avenues available to personnel in the rank and file to prepare themselves for, and try to secure entry into, the officer cadre through the respective officer training academies by going through the appropriate selection processes.

In so far as commissioned officers in the Armed Forces are concerned, there is need for a more imaginative approach. The first point that needs to be made in this context is that the pyramid structure of the Armed Forces hierarchy imposes on the organisation the imperative to have a largely short service cadre of officers who serve for about five to ten years at the junior level of captains and majors that form the base of the structure, and then move out into other avenues of employment. Complementing this is a regular cadre that provides the basic frame and the hierarchy. With the current scales of pay and allowances, it is probably fair to state that there are few problems of getting appropriate volunteers for entry into the regular cadre through the National Defence Academy and direct entry at the respective Service academies. The existing shortfall of officers is at the level of captains and majors due to the fact that the establishment has not been able to attract the youth of the country into the short service category in adequate numbers. This is not surprising as the terms and conditions are rather unattractive to an aspiring youngster. The question the “powers-that-be” should ask themselves is: why should a bright young person who has just graduated from college at the age of 21 or so, aspiring to do well for himself or herself, join the ranks of short service commissioned officers in the Indian Armed Forces, serve for five or ten years, largely under inhospitable conditions, and then, at the age of 26 or 31, set out all over again to look for a place in the highly competitive market place where there is already so much unemployment? The answer to this rather depressing outlook lies in providing those, who after completing the terms of short service engagement are interested, with scope for lateral induction into the central and state government services as also the para-military, central and state police forces, public sector undertakings, etc. with an opportunity to obtain desired skills through management courses or information technology courses, etc, at government expense either before leaving the Service or after. Needless to say, those who are interested in continuing in the Service, should be screened for the purpose and given regular commissions provided they qualify.

Such measures if implemented, will not only be one way of addressing the aspirational needs of defence personnel, but ensure a youthful profile in the Services, significantly reduce the Government’s pension liability, and make available to the wider community in the country, well-disciplined, well-trained and physically and mentally fit human resources with the capacity to deal with difficult and dangerous situations when the need arises. This will be of particular value in terms of trained manpower to the para-military and police forces dealing with insurgency and left wing extremism.

This aspect of “Lateral Induction” of defence forces personnel was one of the major recommendations of the Kargil Review Committee, endorsed in the 2001 Group of Ministers Report, and reiterated by Parliamentary Standing Committees for Defence, as also by the Sixth Pay Commission. Implementation has been stalled by vested interests on flimsy grounds that stand little scrutiny. All that is required are executive directions for implementation. We shall continue to wait with bated breath to see whether the current governing dispensation really has the capacity and the will to take action on this vital issue, rather than indulge in the same rhetoric that we have been subjected to in the past.

( Lieutenant General Satish Nambiar PVSM ,AVSM ,Vr C. (Retd.) of the Indian Army was the first Force Commander and Head of Mission of UNPROFOR, the United Nations Protection Force. The views in the article are solely the author’s. He can be contacted at editor.adu@gmail.com)